The Strangeness of Beauty – Issue 11 – Aline Asmar d’Amman and Sam Samiee

17-23 March 2021

View the full issue

Has the Shock of Strangeness led to One Thousand and One Questions?

The title of this text references a line from Sam Samiee’s writing in this issue of The Strangeness of Beauty and, incidentally, provides an interesting entry into a discussion about an art installation currently showing for two months in the Alpine town of St Moritz, Switzerland. Damien Hirst’s Mental Escapology is mainly an indoor exhibition but also includes some outdoor sculptures, among which are two large works on and around Lake St Moritz. One of these sculptures, Temple, 2008, is a tall 660-centimetre painted bronze which stands forlornly a dozen metres up from the edge of the lake. Like an oversized anatomical model of a male torso, it reveals the body’s musculature and organs. The other piece, The Monk, 2014, last shown in The Wreck of the Unbelievable, Hirst’s 2017 exhibition in Venice, is approximately 380-centimetres-tall and appears to represent a meditating monk sitting cross-legged right out there on the frozen lake. As if after long years underwater, the work, entirely covered by a growth of saltwater corals, algae and barnacles, has apparently just been salvaged from the deep water, though, of course, no saltwater corals could live in the sweet water of Lake St Moritz.

Damien Hirst, Temple, 2008. Installation in St Moritz, 2021 Photograph by Ziba Ardalan.

Each of these sculptures is a representation of the human condition, and to install such works publicly during the challenging times of the Covid-19 pandemic could make perfect sense in that people experiencing their own confinement could surely relate to them. So why is there so little enthusiastic discussion about these works, particularly in Switzerland where debates about contemporary art are often as heated as any about social, political or economic matters? At a time when museums and art galleries are closed, and people have a huge thirst to experience art at first-hand, why have these works not been received with more attention and real controversy? Could the awe-inspiring natural beauty of the valley override the importance of any artwork? Of course, these two works by Hirst have already been seen and read about elsewhere and therefore may have lost something of their novelty – a concept with which our society is infatuated.

The immense Engadin valley is known for its majestically beautiful landscape, quality of light and seasonal scenery, which changes dramatically throughout the year, yet is always unique and awe inspiring. The region is also known for its numerous historic villages, each with its own history, culture, and characteristic architecture, although the town of St Moritz, which is very popular with tourists, has a somewhat jarring mix of architectural styles. Yet somehow the Upper Engadin area as a whole seems to work remarkably well, and often after visiting St Moritz, one is more appreciative than ever of the unified architecture of other villages – all of which may mean that everyone is happy.

Damien Hirst, The Monk, 2012. Installation in St Moritz, 2021 Photograph by Ziba Ardalan.

Every winter, the alpine lakes here freeze and provide a great stage for various outdoor activities and sports. This winter with its abundance of snow has been quite cold, and in the recent sunny weather the lakes have been well frequented. So, what does it mean to so many passers-by to be confronted with Hirst’s Temple and The Monk? Does perhaps an expression of shock need to elicit a strong response, or do the works blend into the surroundings and magnify the natural beauty? After much thought and reflection, I reached the conclusion that either the discordant installation of these works simply adds to the dissonance of St Moritz’s architecture and therefore misses the power to shock, or maybe there is more to be learned curatorially and conceptually from their siting within the grandeur of these mountains. Or, indeed, perhaps we should be glad of the opportunity to encounter any such cultural undertaking.

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director

Sam Samiee

A Practice in Dignity

I ran into A.J. Ayer by chance last night, and we found enough interesting things to talk about that our conversation lasted until three o’clock in the morning. Merleau-Ponty and Ambrosino took part and, in the end, I believe that the transaction took place then, during that conversation.

It so happened, however, that the conversation took a turn such that, everything being in an agreeable place, I had the sensation that I was beginning my lecture; I apologise for making a distinction between a bar and a lecture hall, but such is the embarrassment of beginning.

Georges Bataille, The Unfinished System of Nonknowledge, University of Minnesota Press, USA, 2004

Short pieces are important when they serve as a break into the future, like a shooting star, leaving behind a trail of fire. They should move rapidly enough so that they pierce the present. While we wait, we cannot yet define the reason for this speech. But we know the piece is good when, in its role as a piece of the future, it sets the present ablaze.

Vélimir Khlebnikov, Oeuvres, 1919–1922, L. Schnitzer, trans., Oswald, Paris, 1967

On the shore where Time casts up its stray wreckage, we gather corks and broken planks, whence much indeed may be argued and more guessed; but what the great ship was that has gone down into the deep, that we shall never see.

Anonymous epigraph to Rooms Are Never Finished, Agha Shahid Ali, W.W. Norton & Co., Inc. New York, 2003

Sam Samiee, Traces of edges of many paintings left at the studio, 2018. Acrylic on studio wall. Studio view at Wiessenstrasse, Berlin, 2018. Photograph by Sam Samiee.

The hypothesis is that we are looking for new things because old things are repetitive, and if repetitive and old could solve the problems, we would be content, but as we are not content, we seek new things. But, also, we realise sometimes that the old is just seeping into the new without us realising it. We therefore engage with and rely upon the philosophers, scientists, artists, and the many thinkers whose methods, aspirations and activities would bring us out of our former patterns of repetition, for something new.

As a younger artist, such progressive imagination about the phenomenon of the new got me thinking, through the history of art, that even the strangest art forms could be appreciated for their beauty. Or for something in them, that perhaps could no longer be considered beauty, but that the strangeness itself was something to be appreciated. These convictions led me to enjoy a great deal of the history of arts and ideas of millennials, the different geographies of many lands and thousands of minds.

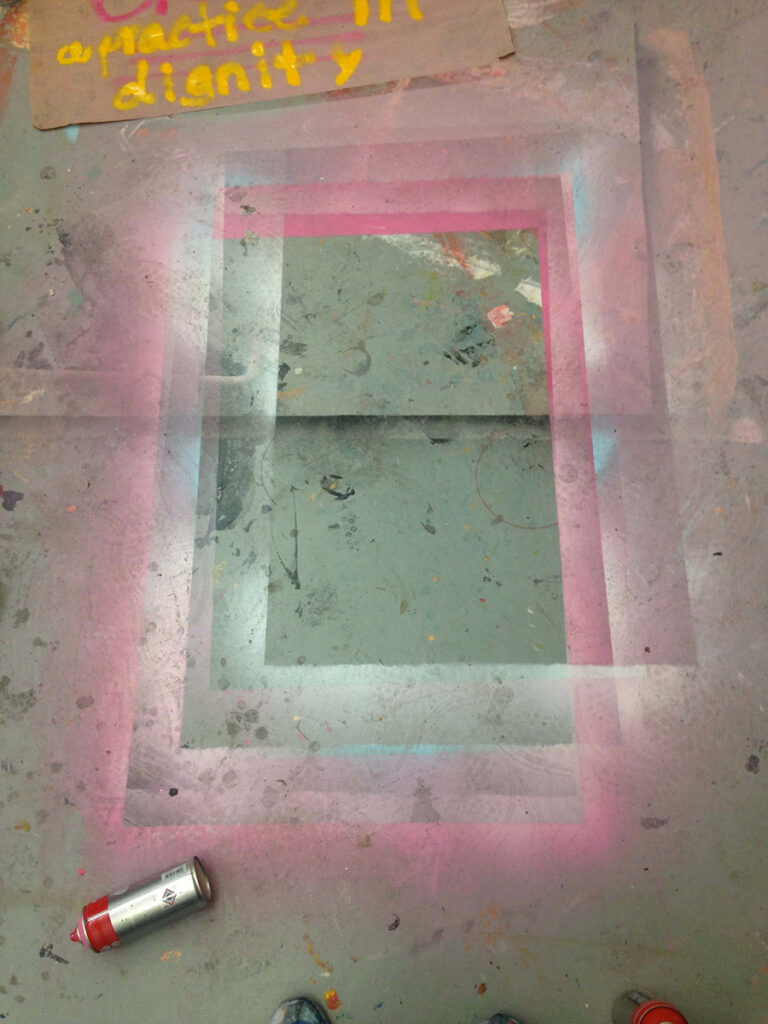

Sam Samiee, A Practice in Dignity, as read on the edge of a draft left on the floor, 2015. Studio view at Rijksakademie, Amsterdam. Photograph by Sam Samiee.

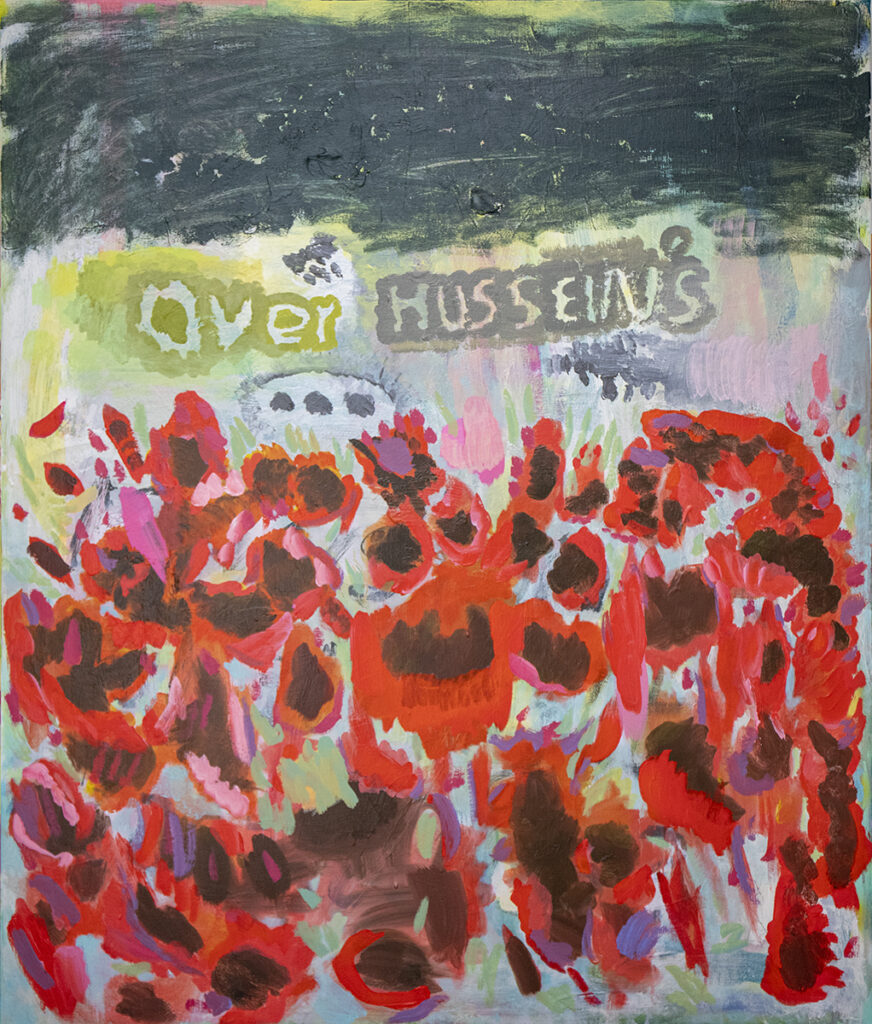

But I must confess that my convictions have undergone a destabilising crisis. Strangeness, shock, counterintuitive and strange conditions on the one hand, and those who have found beauty in much of the history of those conditions, productions, or ideas, which seems to bring us to a point where we find beauty and strangeness not mutually exclusive, at least not for someone of my generation. It might be that alongside my education in western painting traditions I had to indulge in Persian poetry, but also in psychoanalytic thinking, among many other literary and artistic productions, from queer theories to re-definitions embedded in the work of art historians who bring fresh views to our perception of beauty. And among the many, I have to think of two highlights which solidify my convictions to a point of the possibility of a cohering note. One is Pasolini’s film Salò, and the other is the theoretical works of the Bulgarian-French philosopher, Julia Kristeva from whose many ideas her term abject comes to mind. As I type, one crazy association follows, from an Islamic figure, the sister of Hussein, grandson of the prophet of Islam, who upon being asked what she saw at the battlefield on which her brother and closest ones had died to defend their right not to pledge allegiance to the king, she replied, ‘I saw nothing but beauty.’ From which I am reminded of the queer Kashmiri poet, Agha Shahid Ali, whose luxuriantly rich poems make use of Zainab’s words just as he flawlessly embeds them with those of Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Referring to Wittgenstein, Leo Bersani claims that aesthetic and ethical are of the same category. In Receptive Bodies, Bersani’s thought-provoking, heavily theoretical – yet if fully taken in, eventually relaxing and conclusive – reading of Salò, probably the strangest of artworks of our recent past, is called into attention. The pianist’s strange presence is portrayed as the feminist revolt against the symmetry of patriarchy’s fascistic sex-war machinery. Without making it stranger, the conclusion I want to make is one of temporality. To go back to Bataille and Khlebnikov and the convictions of mine in crisis, I shall conclude that the period of engagement might have something to do with the relation of strangeness and beauty. Strange beauty, beautiful stranger, and beautiful strangeness remain explorable based on the timeframe and exploration one affords them. The ideal equation seems to me to be the constellation in which the shock of strangeness has turned into the infinity of seduction, over ‘One Thousand and One Nights’, or more: always as if it is merely an impression left, a trace, unclear whether it is itself part of a bigger picture no longer seeable, or what we shall never see.

Sam Samiee, Over Hussein’s Mansion, What Night Has Fallen? (After Agha Shahid Ali, Rooms Are Never Finished), 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 130 x 100 cm (51¼ x 39½ in). Photograph by Sam Samiee.

Aline Asmar d’Amman

A Walk in the Cave

Cava Arcari, Italy, A page of notebook. Photographs by Aline Asmar d’Amman.

Each virtu has its averse, like the other side of a medal.

From the darkest poisons, experts find remedies to heal illness and disease.

In the tunnels of darkness, every ray of light evokes salvation.

There’s a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in, sings Leonard Cohen in his legendary ‘Anthem’.

In our constant quest for perfection, beauty seizes us in the scorched, the broken, the unexpected strangeness of imperfection. At the crossroads of the unfamiliar and the brutal, the irrational and the emotional reveal the ultimate perception of the beautiful, what we designate as ‘the sublime’.

Whereas the beautiful is limited, the sublime is limitless, so that the mind in the presence of the sublime, attempting to imagine what it cannot, has pain in the failure but pleasure in contemplating the immensity of the attempt.

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, 1781

Kant’s deciphering of the mystical paradox brilliantly translates our understanding of the electrical discharge felt when encountering the sublime. Unchained from the position of judgment related to objective reason, imagination is left free to wander and contemplate, as opposed to decipher and analyse in an impartial manner.

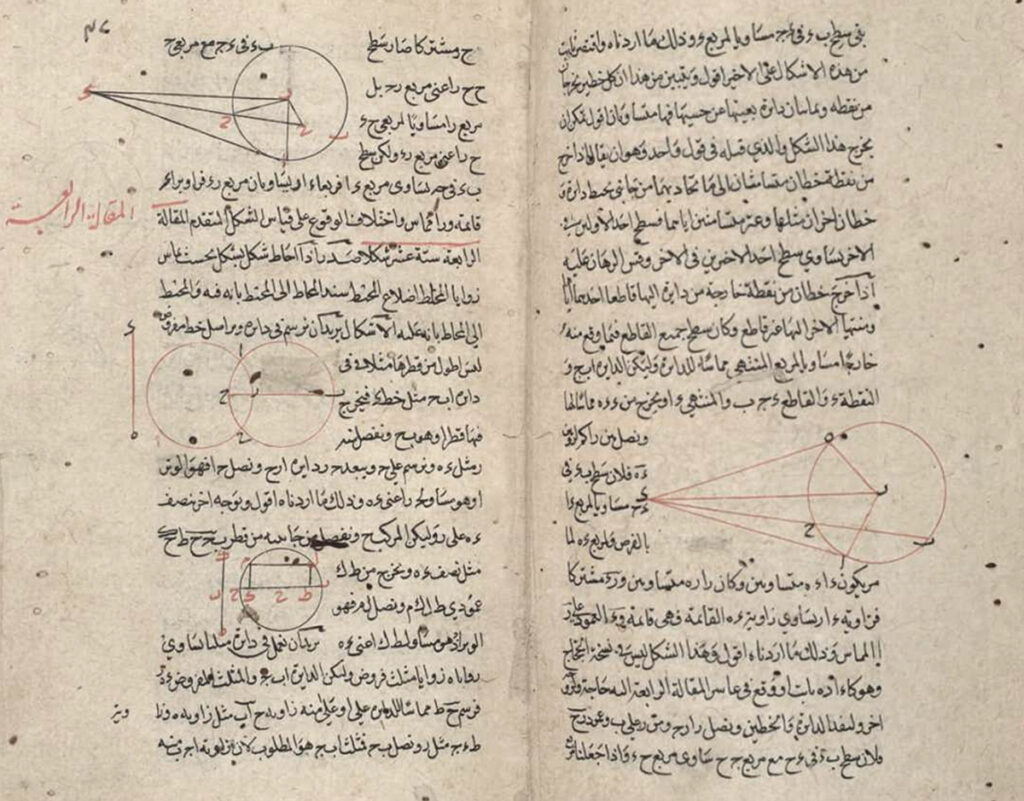

In the everyday practice of creativity, architects and designers look out for the delicate balance between the universally well-proportioned canonic figure, going back in time as far as the founding Greek learnings in Euclid’s golden ratio, third century BC, to the constant evolution of science and technology with regard to the harmonious, the well-being, and the evocative singular artistic qualities of their work. From the first sketch to the material intention, the quest for beauty in all its forms of expression, natural or man-made, is one of the oldest quests in the world.

Arabic translation of Euclid’s elements, created by Persian polymath Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1294).

When in search of the unexpected, my own personal intuition draws me to stone and its infinite landscape of strange beauty.

In my regular visits to quarries, searching for marbles and their particular anomalies to feed my architectural work, the underwater cathedrals constantly evoke Plato’s allegory of the cave, a landscape of silent ruins and personal correspondences between texts and images, material irregularities, scars, veins and crude textures.

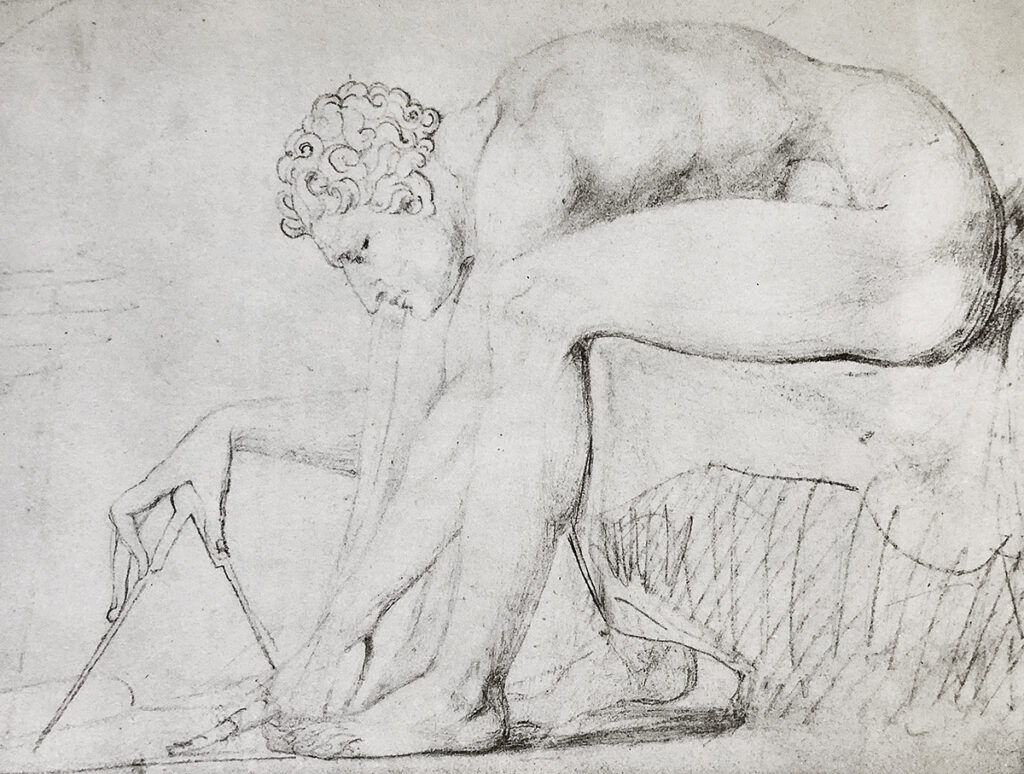

William Blake, Sir Isaac Newton, c. 1800. Pencil study

I often visit with the resonating voices of imaginary literary companions, travelling in the sea of time with the poetic echo of their words.

More recently, it was in the company of three authors that I took a walk in the enigmatic Cava Arcari in Italy, between water, gravel, shadow and mist, reflecting on the power of the material and the fictional, the sensorial and the intellectual, the peace and the terror, the sky, the marble, the universe, evoked in these writings.

The French contemporary author Michel Houellebecq and an excerpt of his poetry publication The Pursuit of Happiness; the American writer of powerful fiction Lidia Yuknavitch and her novel The Book of Joan; and the abstract mystical verses of Mesopotamian poet Muhammad Al-Niffari from the tenth-century Kitāb al-Mawāqif (The Book of Standings) discovered recently and translated into French by Adonis and Donatien Grau.

A dark fairyland atmosphere where beauty is the guest of strange combinations. A walk in the cave with stones, scars and words.

Oscar Niemeyer’s 1963 unfinished architecture for Lebanon’s International Fair. Photograph by Aline Asmar d’Amman.

Burning is an art.

I remove my shirt and step towards a table where I have spread out the tools I will need. I swab my entire chest and shoulders with synthetic alcohol. My body is white against the black of space where we hover within a suborbital complex. CIEL.

Through the wall-size window, I can see a distant nebula; its gases and hypnotic hues make me hold my breath. What a puny word that is beautiful. Oh, how we need a new language to go with our new bodies.

I can also see the dying ball of dirt. Earth, circa 2049, our former home. It looks smudged and sepia.

. . .

I am without gender, mostly. My head is white and waxen.

No eyebrows or eyelashes or full lips or anything but jutting bones at the cheeks and shoulders and collarbones and data points, the parts on our bodies where we can interact with technology.

. . .

CIEL has presented humanity with new bodies: armies of marble white sculptures but nowhere as beautiful as those from antiquity.

Perhaps the geocatastrophe, perhaps one of the early viruses, perhaps errors in the construction of our environment, perhaps just karma for killing the natural world, did this to our bodies. I’ve wondered lately what’s next.

Excerpts reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd © Lidia Yuknavitch, The Book of Joan, 2017

The fine and delicate texture of clouds

Disappears behind the trees,

And suddenly it’s the blur before the thunderstorm

The sky is beautiful, hermetic like a marble.

Michel Houellebecq, La Poursuite du bonheur (The Pursuit of Happiness), © 1997, Librio collection, Éditions Flammarion, Paris, 2020. English translation by Aline Asmar d’Amman.

Ecstasy Beyond Ecstasies

He stopped me beyond the ecstasies, and He told me ‘The universe is an ecstasy’

He told me ‘Every particle in the universe is an ecstasy’

He told me ‘The truth is in the sciences and the temptation is in the judgment of science’

He told me ‘He who attaches himself to the universe, the universe exposes itself to him’

Muhammad Al-Niffari, Kitāb al-Mawāqif (The Book of Standings), 10th century. English excerpt translated by Aline Asmar d’Amman, 2021, from the French Al-Niffari, Livre des extases, translation by Adonis and Donatien Grau, Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 2017.

Next Issue

The Strangeness of Beauty

Issue 12, 24 March 2021

Featuring contributions by

Carlos Garaicoa and Heather Bause Rubinstein