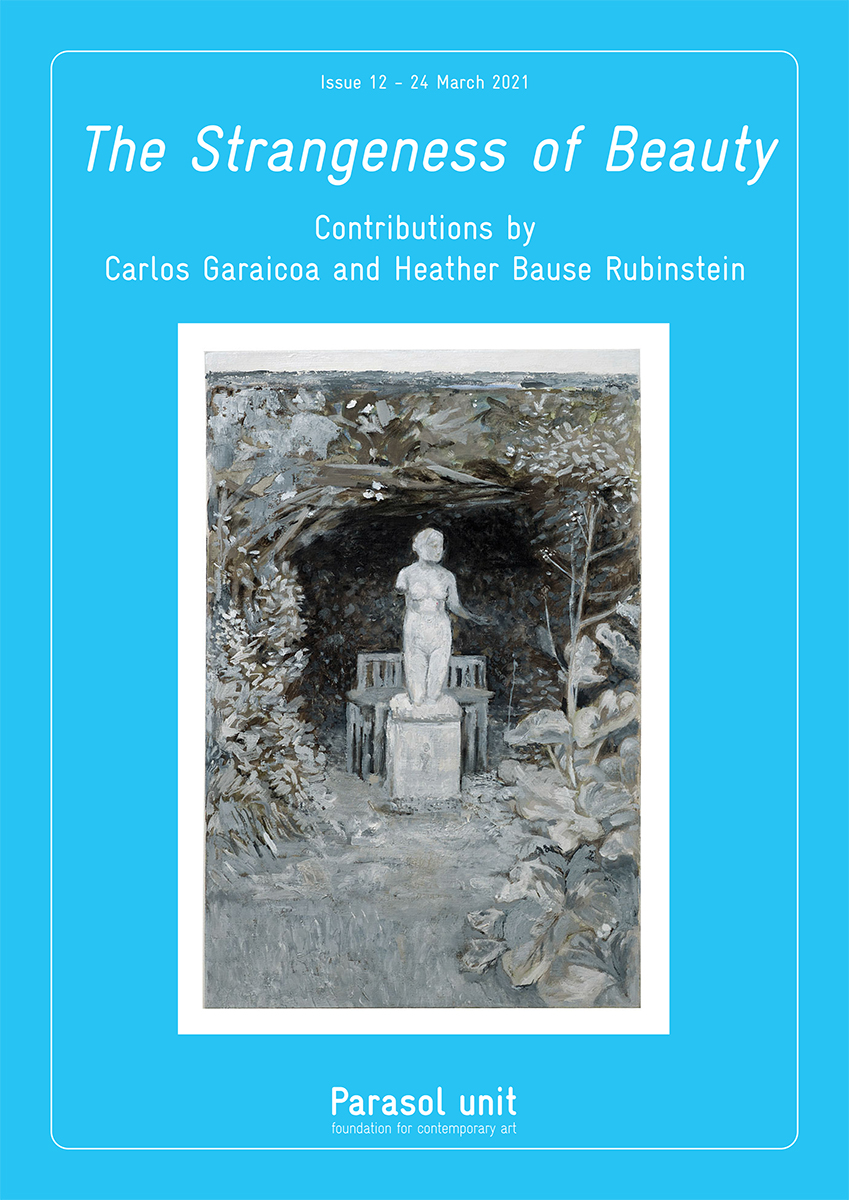

The Strangeness of Beauty – Issue 12 – Carlos Garaicoa and Heather Bause Rubinstein

24-30 March 2021

View the full issue

The Awakening of Our Feelings

For various reasons we decided that 12 issues of The Strangeness of Beauty would be just enough to scratch the surface of this vast topic and to prompt each one of us to individually develop and share our thoughts about it. Issue 12 brings to a close our voyage of discovery and exploration through this fascinating project which, thanks to digital technology, has brought us together and offered us a wider range of perspectives on the subject.

Conceptually, we started our discussion with a quote by Edgar Allan Poe, There is no exquisite beauty . . . without some strangeness in the proportion. The idea has taken us on an extraordinary journey. For example, we have learned that no matter how other people perceive an artwork, the artists themselves always strive to achieve beauty or perfection in their work. Some of the contributions let us see that strangeness in beauty can come our way naturally in often overlooked objects or places. We were shown that at times we are forced to find beauty in strange things by the sheer experience of being faced with them. Remarkably, we discovered that strangeness and beauty could be interchangeable, as for instance in kitsch items. Other thoughts made us aware that strangeness can become evident when we have the courage to explore new areas. We plainly saw that there was beauty to be found even in something shocking. Miraculously, we discovered that unexpected circumstances could lead to strange and beautiful situations. We marvelled that external influences, such as time, could make something uncanny and strange, yet beautiful too, especially if we allow feelings to enter the game. Had we ever thought that strangeness is indeed integral to the process of reaching beauty? It was interesting to discover that unexpected strangeness or beauty in an artwork is likely to have arisen unbidden through the process of making. I certainly never consciously thought about the extent to which our three powers of the soul could be instrumental in our perception of beauty, but I am grateful to have learned it. Having expanded our understanding of the notion of beauty and strangeness, it was natural that we also explore the awe-inspiring concept of the sublime. Generally, philosopher Immanuel Kant is credited with differentiating between beauty and the sublime in his 1764 Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime. However, the eighteenth-century Irish statesman, economist and philosopher Edmund Burke, in his 1757 publication A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origins of our Ideas of the Beautiful and the Sublime, had already extensively discussed the difference. To make things more complex, it is interesting that we also explore the distinction between the nature of strangeness in beauty and uncanniness in the sublime. We understand that the terrifying, the unfamiliar and strangeness are considered to be inherent in the concept of the sublime, while not all the strangeness we encounter can be defined as sublime.

I am more than ever grateful to all of those who with grace and generosity agreed to contribute their ideas and images. As issue after issue unfolded, I realised how little I knew about the concept of strangeness in beauty, how much I was learning and, yes, it was an enormous amount! Preparing each issue and writing an introductory text for it has led me to reflect ever more deeply about myself: who am I as a person, and have I done enough to nurture my senses and the power of my soul to express itself and to thrive? Certainly, the Covid-19 pandemic made all of us rethink a lot, and I have read and heard many people speak of the beneficial aspects of it. If this is true, then what was wrong before? We know that to live harmoniously we should make use of all our five senses – sight, hearing, touch, taste, smell – as well as the three powers of the soul – intellect, will and feeling. Clearly, prior to the pandemic, we were all leading busy lives, almost to the point of abusing some of our faculties, one of which may have fallen short or been neglected. Could this have been feeling? While reflecting on that, I came across an incredible book by Antonio Damasio, The Strange Order of Things,¹ which explores life, feeling and the making of cultures:

Why and how we emote, feel, use feelings to construct ourselves.

How feelings assist or undermine our best intentions.

Why and how brains interact with the body to support such functions.

Reading further, it seems clear to me that while the progress or development of our world has made us amply use our intellect and will, our feelings have not been given the attention and thought they deserve, and we now need to take them seriously.

Indeed, during the periods of lockdown, when we had extra time, we began to think more of family members, friends and acquaintances, and to feel sympathy for those in pain or suffering. In reality, this meant that our feelings were communicating with our brain and prompting us to act. As Damasio explains, feelings are not simply a fabrication of our brain or, as many think, of our heart, but rather they result from cooperation between body and brain. Feelings dominate us, they make us want to look good, to be successful, to be admired. Feelings act upon our psyche and make us upbeat or fearful. In the everyday life of the financial world, for example, they contribute to whether the stock market goes up or down. Our feelings recognise for us who we appreciate or love or, on the contrary, despise. I know we are entering an inexhaustible area of discussion – so for now it may be wiser to introduce the thoughts and works of the two artists, Carlos Garaicoa and Heather Bause Rubinstein.

Once again, I take this opportunity to thank every single one of you who has accompanied me on this incredibly enriching exploration and I very much look forward to documenting our work in a printed publication. As ever, I remain indebted to my invaluable collaborators. My gratitude goes to Helen Wire, our astute and patient copy editor; Kirsteen Cairns, for the attractively designed issues and their layout; Karl Schenker, for his positive can-do attitude; and for her assistance, Sophie Moiroux who has recently joined our team.

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director

¹ Antonio Damasio, The Strange Order of Things, Pantheon Books, div. of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, 2018.

Carlos Garaicoa

From the Garden

It all began the day I had the feeling that something terrible was going to happen. I can’t pinpoint what led me to experience such a fear, but a feeling that something didn’t quite add up within the perfect algorithm of my garden wouldn’t stop tormenting me. Perhaps I was the only one capable of perceiving the danger, being as I am hyper aware of space and, above all, sensitive to the slightest change in that piece of land.

Let me tell you a little about myself. From a very young age, I knew that I had a perfect understanding of any space or place I was in. My bedroom, the living room at home, the classroom, the school cafeteria, as well as any type of building or landscape: parks, gardens, lakes, forests – anything involving a map or line guarded my secret.

This natural understanding of my surroundings affirmed my childhood passion for mathematics, architecture, and complex musical harmonies. That absolute consciousness of the order of things became an obsession, which in turn became painful and, later, an unbearable burden.

When I was young, I decided to study architecture and explore this academic degree which promised to provide an answer to my natural calling. I intended to alleviate my burden by studying an array of structures and building methods. Then, disappointed by the futility of my eagerness to gain technical knowledge about what I already knew empirically, I decided to

quit studying.

Around that time, I received a substantial inheritance. I went from university dropout to having complete freedom, with no ties or social obligations. Money, a good house and a large yet soulless plot of land became the focal point of my life. I must admit that the bareness and hideousness of that plot of land provided a good incentive for my lack of interest in studying.

I decided to convert that plot into a garden that would be the most perfect, refined, and complex garden ever, mathematically and aesthetically speaking.

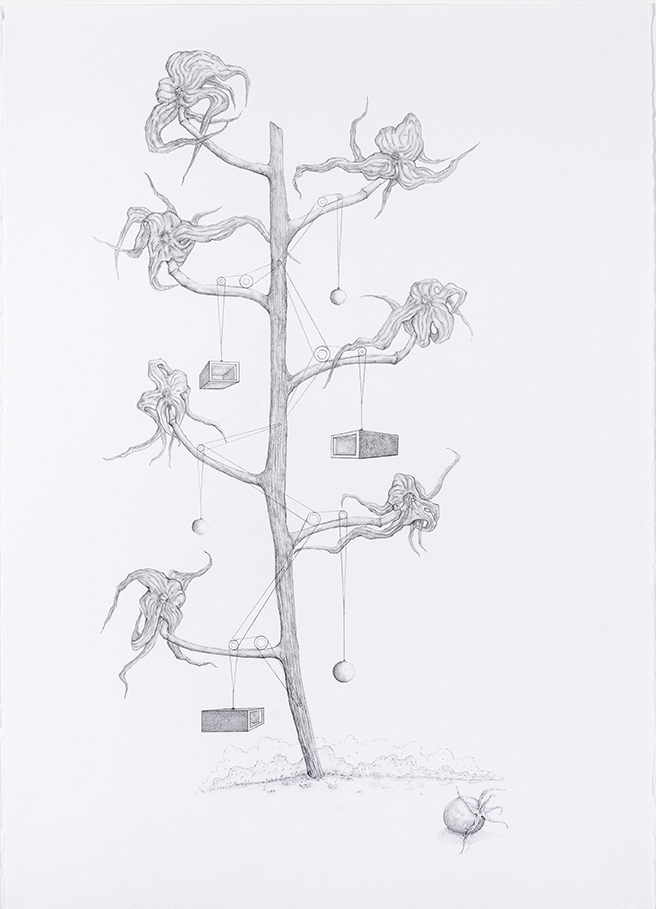

Carlos Garaicoa, From the series Models C (Model C-X), 2020. Graphite drawing on Guarro cardboard 240 g, unique work, 70 x 50 cm (27½ x 19¾ in). Photograph by Oak Taylor-Smith.

My tenacity kept me going for the next 20 years. Studies about gardening in Egypt, Mesopotamia, China and Japan blended together with many treatises on the symbolism and philosophy of Byzantine gardens and the efficacy of irrigation and canals in Arabic engineering; and not without regard for the complex botanical codices from which I learned about the healing properties of every single plant and flower in existence.

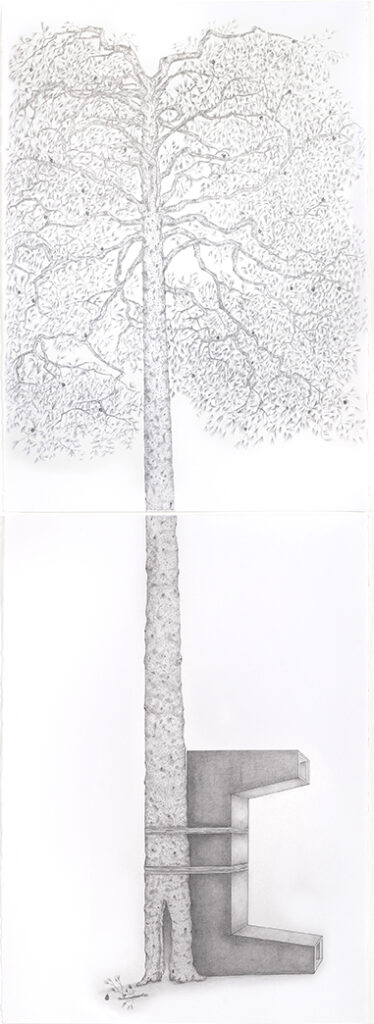

Carlos Garaicoa, From the series Models C (Model C-XIV), 2020. Graphite drawing on Guarro cardboard 240 g, unique work, 70 x 50 cm (27½ x 19¾ in). Photograph by Oak Taylor-Smith.

When it came to gardens, nobody had ever reached such perfection, such harmony or such an expression of the meanings of nature, mastered and controlled by the hand of man. At last, I would have a space I could roam around comfortably without any eyesores. My garden would be (and was) the true expression of Heaven on Earth.

On that fateful day of my premonition, I discovered new protuberances and prominences in the land. I noticed changes in the inclination of the ears of wheat, and I could also see that some of the ferns and plants had surpassed their official height by some millimetres.

These signs, in addition to a slight change in the scent of the bare earth and lavender flowers and the excessively saturated colour of the grass, drew my attention to almost imperceptible crystallisations on the tree bark, adding to the chaotic compendium of anomalies that confirmed my suspicion that imminent danger was on the horizon, or at least that’s what I could sense.

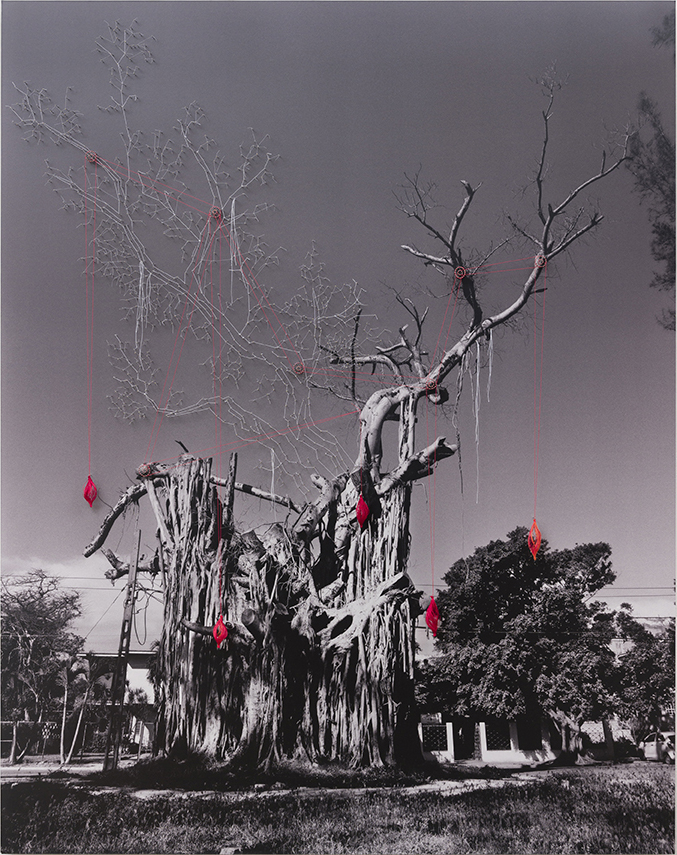

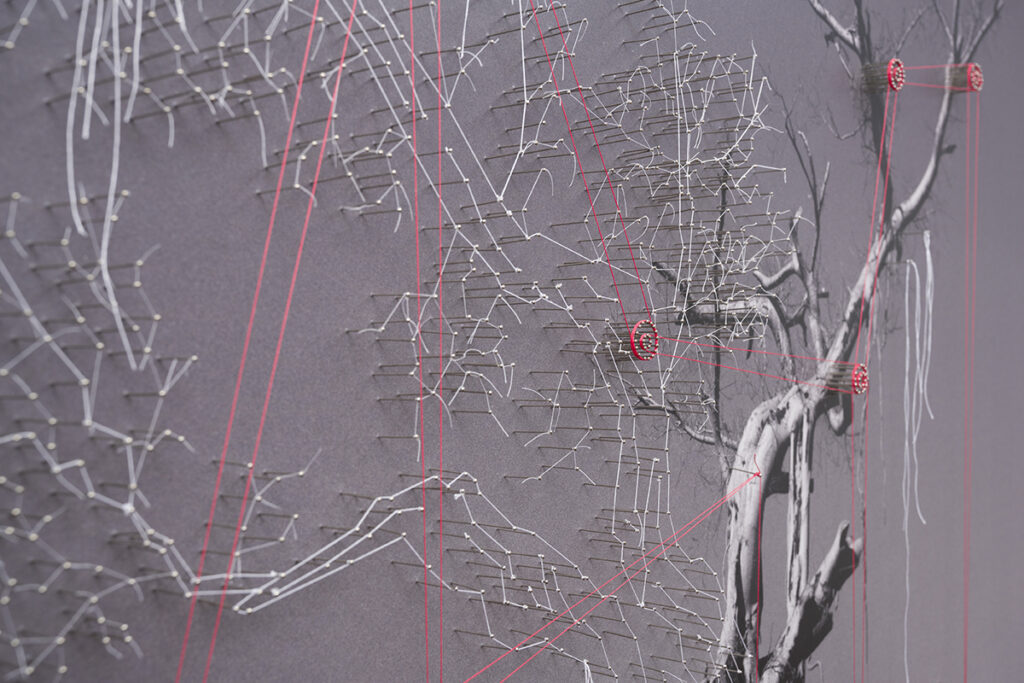

Carlos Garaicoa, Untitled (Tree), 2021. Pins and threads on lambda photograph mounted and laminated on black Gator Board, 157 x 124 cm (61¾ x 48¾ in). Photograph by Oak Taylor-Smith

I imagined endless and meandering gardens, full of robust trees that, although dead, grew luscious, poisoned and beautiful fruit. In my mind, I designed small basins of constantly changing sweet liquids and juices mixing with one another in no particular order and without a recipe, and at the same time, scents of refined and oversweet elixirs, ready for a party where violence and eroticism would meet in the most remote confines of the perfect creation . . .

None of this had happened yet, it was just a premonition, and therein lay the most terrible part of the story. My exhaustive knowledge of the prevailing order would confirm that everything was in danger, and that my reality was faltering. It was the undeniable alignment of my body with the physical spaces that recognised the beginning of an orgy that nobody could avoid, and nothing could control.

In my mind, I just went over and over a future of distant and wasted images, and the odd anecdote told here or there about those hectares of dry and dismal land, where the infinite Sap of Human Nature, Knowledge and Perfection once roamed free.

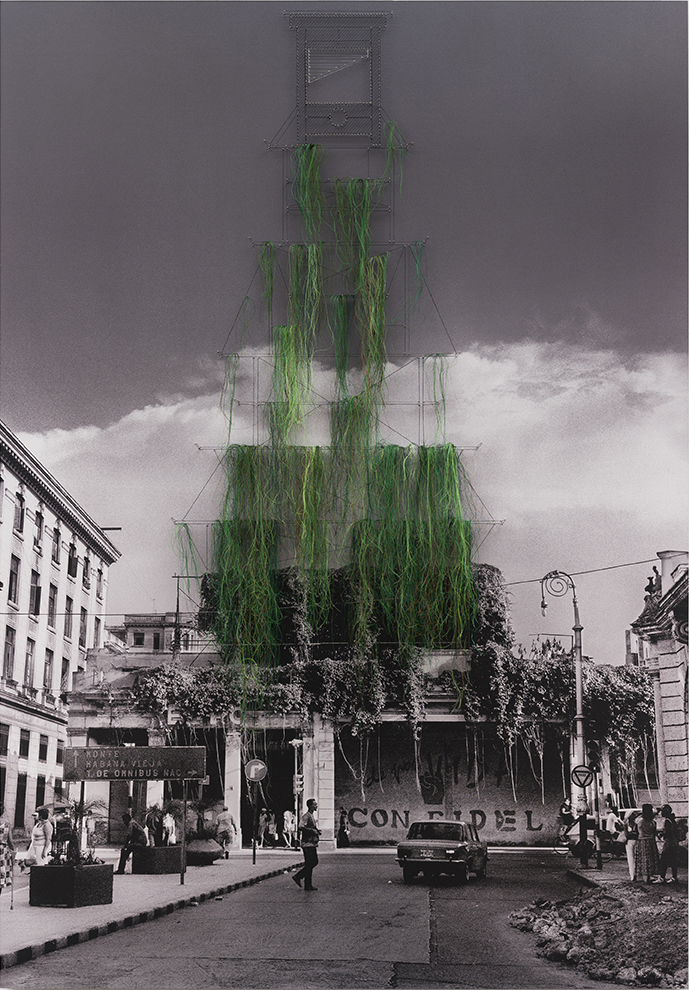

Carlos Garaicoa, Untitled (Vertical garden and guillotine), 2021. Pins and threads on lambda photograph mounted and laminated on black Gator Board, 178 x 124 cm (70 x 48¾ in). Photograph by Oak Taylor-Smith.

Carlos Garaicoa, I’ve never been a surrealist until today, 2017. Site specific work at MAAT, Lisbon. Photograph by Oak Taylor-Smith.

Heather Bause Rubinstein

Like Love

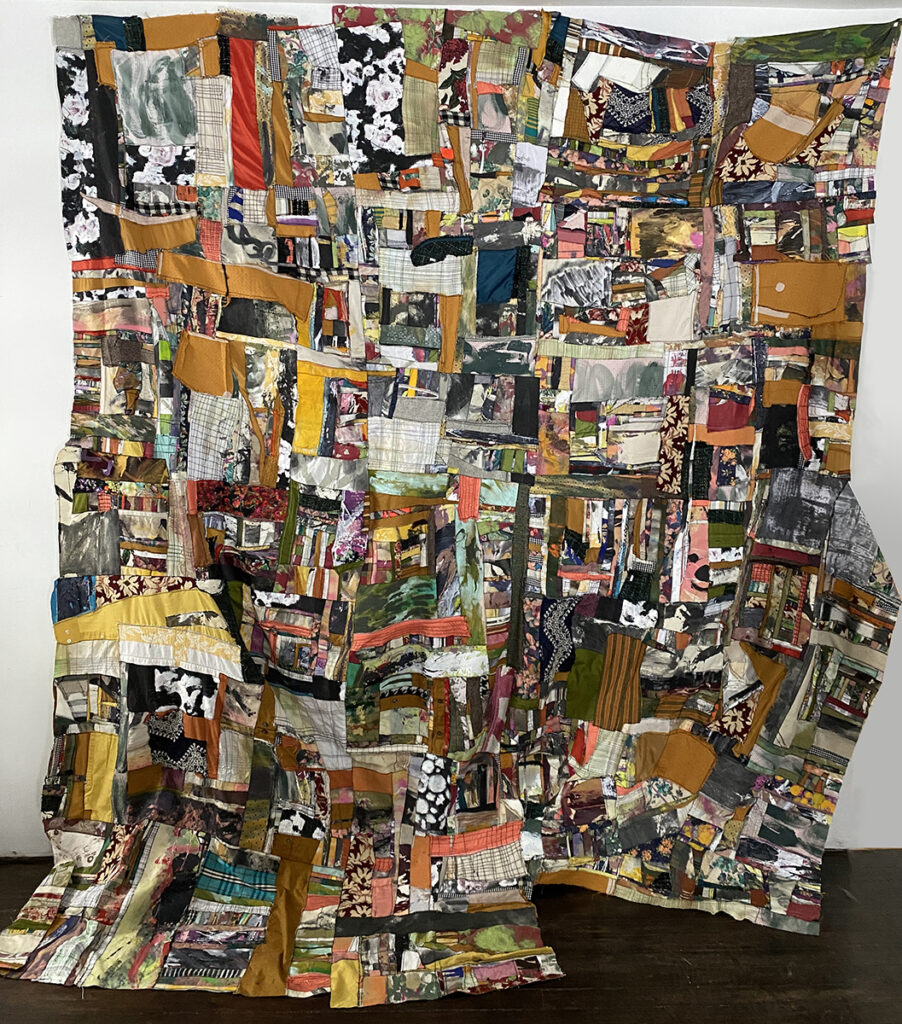

Heather Bause Rubinstein, The Clockwork (installation in progress), 2020–21. Painting fragments, latex paint on recycled textiles, thread, 670 x 303 cm (263¾ x 119½ in). Images courtesy of the artist.

It’s the middle of winter, the worst one in years. It is also the middle of a pandemic, or maybe not the middle but only the beginning, or maybe it’s close to the end. No one knows. In a quiet studio, surrounded by stacks of folded cloth, Heather Bause Rubinstein is working with a pair of scissors and a sewing machine, cutting up and stitching together countless fragments of fabric. Their sources are even more diverse than their irregular shapes: curtains, bedsheets, dish-cloths, women’s suits, embroidered tablecloths, brocade upholstery, scarves, men’s long-sleeved shirts, knitted blankets . . .

Frequently interspersed in this panoply of thrift-store finds are cut-up pieces of her own gestural paintings, which themselves are invariably made on recycled domestic fabrics. Although most of the fabrics the artist utilises derive from the shopping-mall America of her childhood in the 1970s and 1980s, she is even more inspired by the mobile cloth-and-wood shelters of the nomadic peoples of Central Asia.

Feeling overwhelmed by the violence and intolerance that has beset her country for years, and anguished by the invisible threat of a deadly disease all around her, she no longer feels it is sufficient to make paintings to hang on walls where they can be looked at from a polite distance. She wants to be able to offer something different, a more immersive rapport between the body of the artwork and the body of the viewer. What she envisions as she patiently, meticulously, cuts and stitches and sews is the painting as a room, an envelope, a blanket, a shell, a cave, an embrace, a home, a refuge, if only for a moment or an hour.

Once her many hundreds of pieces have been assembled into a single enormous cloth, with miles of stitching and a kaleidoscope of colours, patterns and textures, something will be generated, she hopes, for whoever enters the enveloping mosaic of her painting-tent, something, she hopes, like love.

Raphael Rubinstein

We, at Parasol unit, would like to thank all the contributors to The Strangeness of Beauty who made this online project possible:

Maria Thereza Alves • Carla Arocha and Stéphane Schraenen

Aline Asmar d’Amman • Heather Bause Rubinstein

Oliver Beer • Luca Berta • Aaron Cezar

Richard Deacon • Jimmie Durham • Cecilia Edefalk

Carlos Garaicoa • Francesca Giubilei

Thomas Hirschhorn • Katy Moran

Si On • Raphael Rubinstein • Sam Samiee

Rayyane Tabet • Jakub Julian Ziółkowski