The Strangeness of Beauty – Issue 10 – Richard Deacon

10 - 16 March 2021

View the full issue

Could Strangeness be in the

Sheer Realisation of Beauty?

George Santayana, 1863–1952, was a writer, poet, novelist, but above all, a philosopher, whose sense of beauty has been described as second only to Plato’s.

His book The Sense of Beauty, published in 1896, following a series of lectures he gave at Harvard College, is a revelation of his thoughts on beauty. Santayana asks many questions: why, when and how beauty appears, what conditions an object must fulfil in order to be considered beautiful, what elements of our nature make us sensible of beauty, and since beauty is in the eye of the beholder, what is the relation between the constitution of an object and the excitement of our susceptibility to it? This susceptibility will, of course, decide if and where there is any strangeness within the beauty. To elaborate on the latter, one must admit that whether we want it or not, we have in us some elemental instinct that is interested in beauty. What we need to find out is how to define such an instinct.

Santayana then strives to deconstruct the act of recognising beauty into judgement and perception, in which could lie a sense of imperfection. For him, all human senses – sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch – as well as the three powers of the soul – intellect, will and feeling – contribute to the sensing and judging of beauty, that feeling of having experienced something good. Andrew James Taggart in his article ‘Do we desire what is good, or do we call good what we desire?’ notes that both Socrates and Aristotle say that we desire what is good, while Spinoza and Nietzsche thought we call good what we desire. Naturally, which of those is correct depends on our understanding of the question, on our concept of beauty and our judgement.

For Santayana, beauty is a value rather than a perception of matter, fact, or relation. It is an emotion, which is positive, a sense of the presence of something good. As we saw in Issue 8 of this digital publication, The Strangeness of Beauty, emotion was beautifully expressed by artist Oliver Beer when he revived memories of his grandmother, ‘Oma’, through the physical traces of her life impressed over years into the linoleum that had covered her kitchen floor, or the emotion of singing into an object and listening to it singing back to him.

Emotion seems a new word in a world dominated by cognitive thinking and behaviour. When was the last time you read or heard that emotion – that very deep inner feeling – was enormously superior to any precious physical object you used to admire, or deep down you had really wanted to possess? What does all this say about us, our humanity, or human values? How many times in your own life have you heard that in the face of life’s reality, emotions ought to be dissipated in the background, since they distract from all cognitive preoccupations and logic? Did our individualistic and disconnected life in the pre-Covid years gradually supress our emotions? Has this powerful pandemic finally reminded us that we are indeed human, that we possess emotions and need to be considerate of them? For sure, and whether my opinion counts or not, I know that only when we do, will we be able to consider ourselves human.

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director

Richard Deacon

Surprisingly Beautiful

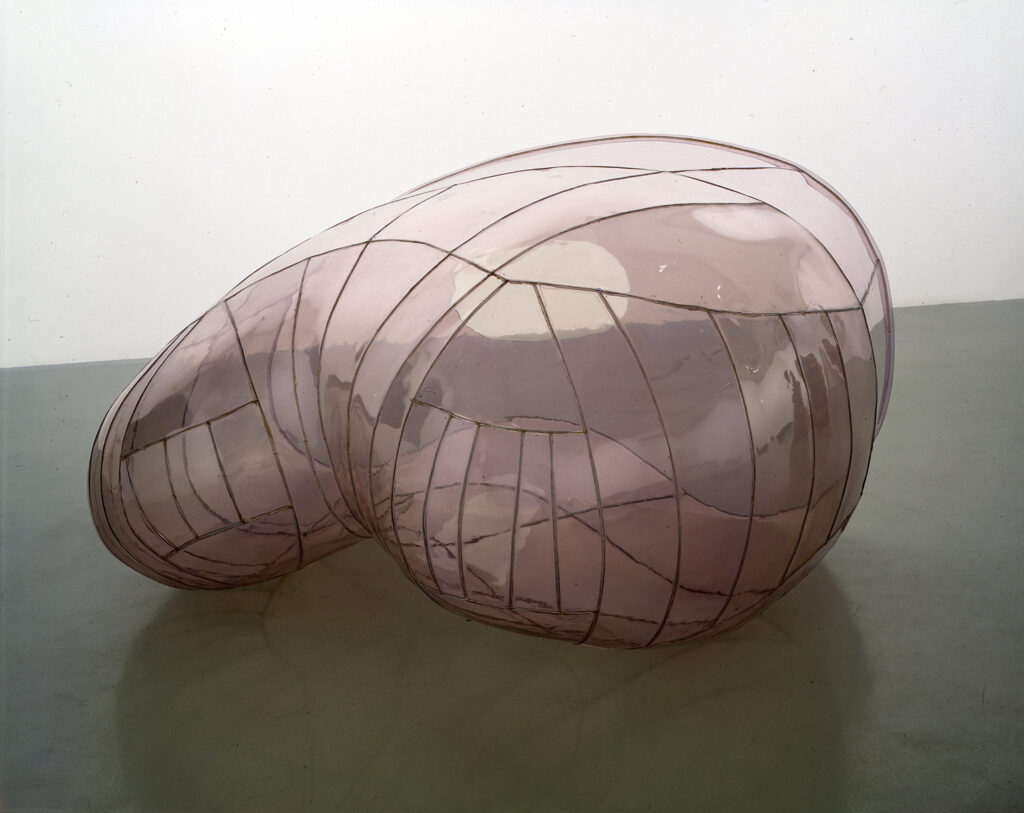

Richard Deacon, Pack, 1990. Welded PVC, 217 x 253 x 159 cm (85½ x 99¾ x 62¾ in). Courtesy of Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo, Norway. Photograph by Volker Döhne.

I have made many sculptures by bending or folding, then fixing a thin sheet or strip of material, and built a lot on what happens – that is, when you bend something, you also stiffen it. In the early 1990s, I began to feel a bit constrained by the fact that this stiffening is only in a single plane, whereas making a three-dimensional form needs careful assembly. If you like, it’s a tailoring problem, bodies are curved, cloth is flat, sophisticated cutting and joining is required to make the material fit without puckering or gathering. Another way to put it is to say that it is the cartographic problem in reverse – the surface of the Earth is curved and maps are flat, any projection of one onto the other is a distortion. Anyway, I was looking for ways to escape from this constraint and casting around for material practices that would enable me to work with a curved volume – as, for example, a blacksmith would do – when I read something about plastic welding. The heavy trim on modern cars is designed to be sacrificial on impact, but it is also very expensive to replace. Cracked pieces could, however, be repaired by a simple process of welding, using a hot-air gun and a welding rod of a compatible plastic. The result is a true weld – there is molecular continuity across the break. Of course, this is attractive to vehicle repair shops but has also spawned a whole craft industry associated with welding plastic forms from scratch. Learning about this opened the possibility of my joining complex curves together in the studio. I could make components by heating small segments of plastic sheet in an oven and forming them over a shape. The resulting fragments could be welded together along the lines where the fragments met. Heating and forming stretches the material slightly so the surface is curved in a complex way.

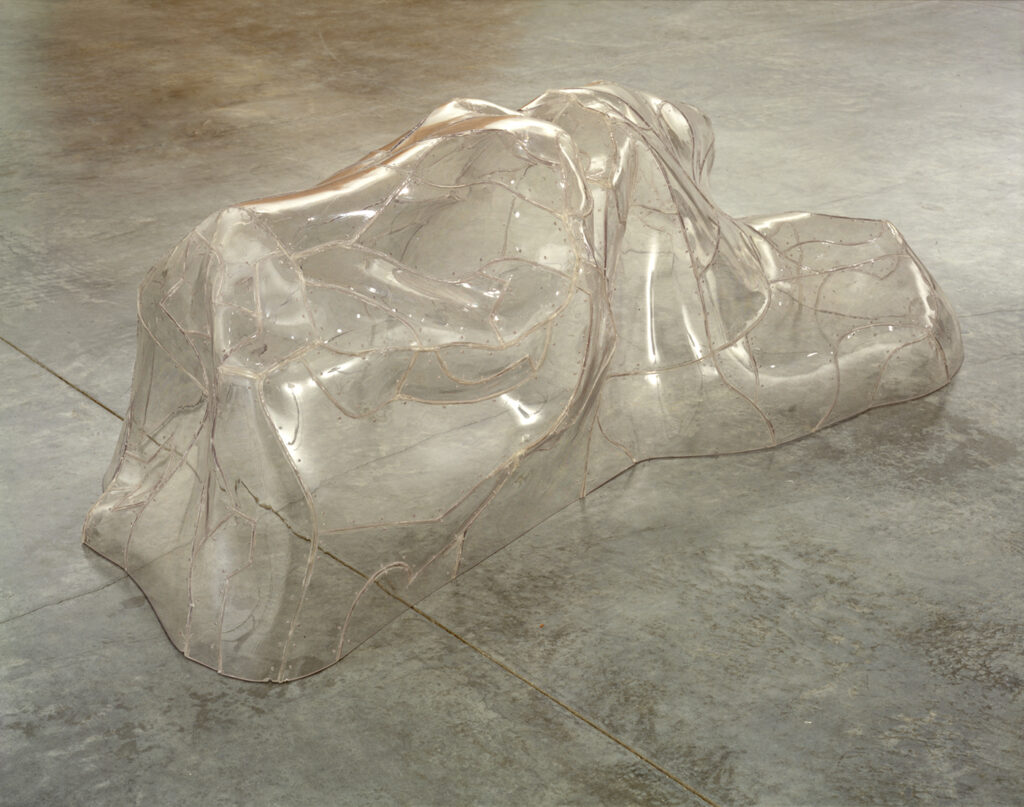

I started off using a sheet of grey PVC that I had in the studio but swapped to using a clear version of the same material as I began to understand the process and to think I was getting somewhere with it. Making something that was transparent was much more interesting – the network of welds joining the segments together becoming very much a drawing that describes the object it is. [Coat, 1990, p. 7]

Coat, under construction, 1990. Richard Deacon studio photograph by Susan Ormerod.

Richard Deacon, Coat, 1990. Welded PVC, 122 x 213 x 183 cm (48 x 84 x 72 in). Private collection. Image courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York. Photograph by Michael Goodman.

It worked and I was excited but there were problems with the material – heating PVC gives off toxic fumes. I stopped and searched for an alternative thermo-formable and durable plastic available in sheet form. This took a while, but polycarbonate seemed ideal – the technical literature had a photograph of someone throwing a brick at a polycarbonate enclosed bus shelter, suggesting its durability on the mean streets! PVC, for all that the sheet I was using was technically transparent, in fact had quite a strong violet colour cast.

[Pack, 1990, p. 4]

The polycarbonate, when it arrived, was protected by a thin cover sheet. Once this was removed the material was revealed to be crystal clear. To my surprise, and delight, I realised that I thought the material was in itself beautiful. I have from time to time remarked that water, coming from the tap into a galvanised bucket, is beautiful. ‘One of my favourite things is clean water in a galvanised bucket because there’s some extraordinary way in which the clarity of the water describes the volume of the bucket. There’s a marvellous clarity where the surface of the water is present and absent at the same time. The volume of water . . . highlights that beautiful silvery zinc colour of the bucket. A real crystalline light is present and captured within it. All it is, is water in a bucket.’ (RD, quoted in Richard Deacon, Reef, Städtische Museen Heilbronn, 2019.) This crystal quality seemed inherent in the polycarbonate sheets, they made the studio sparkle.

Inevitably, once we started work – cutting, drilling, heating, bending and welding the plastic – some of that quality was lost. A certain gap developed between what the material was and what it became, and this gap in itself generated some of the meaning I felt could be attached to the works and to my interest in continuing with them. At some point, when we were making one of these – and it was always a two-person process – my assistant was inside the form welding the pieces together and I realised that there was something immanent about how it looked, in a science fiction sort of way – Invasion of the Body Snatchers perhaps or Bride of Frankenstein. The titles, Not Yet Beautiful, 1994, and Almost Beautiful, 1994, two of the most ambitious works I made with polycarbonate in the period, reflect the existence of that gap which had given me pause for thought and is, after all, an existential one between being and becoming. The beautiful is also in there somewhere.

Richard Deacon, Almost Beautiful, 1994. Laminated wood, welded polycarbonate, 190 x 360 x 95 cm (75 x 141¾ x 37½ in). Courtesy of Kiasma, Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, Finland. Photography by Antti Kuivalainen.

Richard Deacon, Not Yet Beautiful, 1994. Welded polycarbonate, 70 x 210 x 120 cm (27½ x 82¾ x 47¼ in). Photography courtesy of L.A. Louver Gallery, Venice, CA, USA.

Next Issue

The Strangeness of Beauty

Issue 11, 17 March 2021

Featuring contributions by

Aline Asmar d’Amman and Sam Samiee