The Strangeness of Beauty – Issue 9 – Aaron Cezar and Cecilia Edefalk

3 - 9 March 2021

View the full issue

The Path of Strangeness to Beauty

Reading the various texts so far contributed to The Strangeness of Beauty project, I realised how similar and yet different are the thoughts expressed by Aaron Cezar and Cecilia Edefalk on the subject. Edefalk as an artist and Cezar as a curator, artist and art professional, both include the element of time in their concept of beauty and strangeness and their works almost have a tendency to verge into moving image. Cezar’s dripping tap is described in his text as a contemporaneous accompaniment to his writing and as a totally separate artwork executed by two artists, which eventually turns into a functioning clock, and both can live on as long as no one intervenes to stop them. Interestingly, in the process, the odd existence of both manifestations of the dripping tap finally ingratiate themselves into something likeable, intriguing and acceptable. Edefalk’s paintings of people never follow a classic path and never look entirely rational. As the artist herself explains, there may be a crack in the paint or a hole in a canvas, which makes a painting look odd, but these are necessary and allow the viewer to engage intimately with the work. It is precisely through such dialogue that the oddity and strangeness in a work becomes something familiar, something that can be aesthetically appreciated.

Edefalk’s latest works, such as Dandelion Blue show a new direction in her artistic concerns, yet the oddity somehow remains. As the artist herself mentions these later works are concerned with light and darkness and are painted with thin layers of watercolour on paper. They are the works of a mature artist with many years of experience and therefore are no longer preoccupied with details. On the contrary they manifest her generosity, love and metaphysical interest.

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director

Aaron Cezar

Only Time Will Tell

Dear Ziba,

I am finding it difficult to compose my thoughts after being up all night. You see, I have been living with a leaky tap for a year now. Weirdly, I find the sound comforting, most times. I am often drawn to things that repel others – objects, sounds, smells – that are described as ugly, odd, upsetting, or off. I find myself fighting against my own repulsion as I try to understand these feelings of unease. In this search for meaning, I usually discover something about myself or the world around us. I feel as if I unearth some sort of truth that, in turn, creates a sense of balance or harmony. It can also be a transformative experience: what was deemed ugly becomes beautiful, the odd becomes familiar and, well, you get the point.

Throughout the history of art, beauty has been associated with balance in terms of symmetry, space, colour, light, and form. In contemporary art, the issue of beauty is more complex, particularly in political art and social practice. Just like a constant drip, contemporary art practice is dogged by questions such as: When is it appropriate to manifest harmony among depictions of social injustice, violence, and gore? Who has the right to culturally reappropriate and aestheticize images that may be exploitative of others? In a way, these all refer to the entangled notions of beauty and strangeness.

The dripping started again, and now I’ve lost my train of thought.

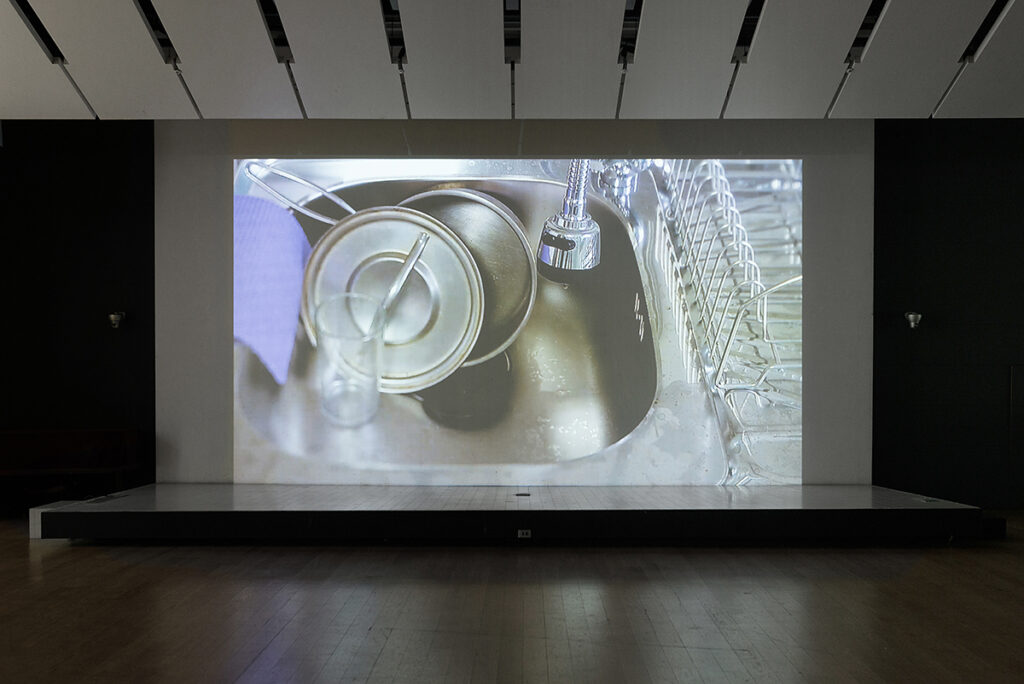

You might be asking why I haven’t fixed the tap. The truth is, it reminds me of an artwork that I commissioned in Seoul in August 2018. For the exhibition, I paired artists to make a new work together for the first time, exploring power dynamics through collaboration. Korean artist Jungki Beak and Dutch artist Jasmijn Visser, who met in 2015 during a residency at Delfina Foundation, created a series of new works called The Stopper, which reflected on the subject of time. There were several inspirations behind The Stopper but most relevant to this story was a leak in Beak’s own flat that seemingly beat at regular intervals of once per second. This prompted Visser and Beak to create a sculpture that appeared as a leaky kitchen tap but operated as a clock. In the exhibition, the artists presented a live stream of this ‘water-tap-sculpture’ that was constructed in Beak’s flat in Seoul and broadcast into the SongEun ArtSpace for the exhibition and later into Delfina Foundation during the London run of the show. The artists described the work as a ‘confrontation with the passing of time’, and in London this was an audible experience. Visitors would first hear a sound of tapping upon entering Delfina Foundation, but they would not see the live stream projected from Beak’s flat in Seoul until the very end of the group exhibition. The layout was designed so that visitors had to then double back through the space, walking through the show in reverse with this new association to time, which in turn had shifted their understanding of all the other artists’ works as well. Many visitors used the word ‘beautiful’ to describe the experience, which I found interesting as many of them had at first been annoyed by the persistent sound.

When I recently asked the artists about the concept of beauty in relation to The Stopper, they discussed the notion of elegance in mathematics, which defines how complexity is comprehended and presented, ‘an elegant proof’ as it were. The artists wanted to represent the complexity of time without reducing or abstracting it, and elegance seemed to be the answer. They turned to mathematics rather than art, even though aesthetics is debated within both areas.

I am not sure if I have responded to your questions completely, but perhaps a key takeaway from this note is that the notion of beauty and strangeness cannot be fully understood without the consideration of – and maybe even a confrontation with – time.

I could ramble on, but the tap is dripping again.

Stay safe. Aaron xx

Aaron Cezar is the founding Director of Delfina Foundation, where he develops, curates and oversees its interrelated programme of residencies, exhibitions and public platforms.

Jasmijn Visser and Jungki Beak, The Stopper, 2018. Installation view, Delfina in SongEun: Power Play at SongEun Artspace, 2018. Photograph courtesy SongEun ArtSpace.

Jasmijn Visser and Jungki Beak, The Stopper, 2018. Water-Tap-Clock, in situ in Jungki Beak’s flat, Seoul, 2018. Photograph courtesy Jasmijn Visser and Jungki Beak.

Jasmijn Visser and Jungki Beak, The Stopper, press image. Photograph courtesy Jasmijn Visser and Jungki Beak.

Cecilia Edefalk

Only Time Will Tell

Cecilia Edefalk, The Bee Girl, 1988. Oil on linen, 192 x 135 cm (75½ x 53 in). Photograph by Carl-Henrik Tillberg.

The oddity that exists in my artwork is not planned, it arrives as part of my creative process. I always want to leave some kind of opening in a work. It is sometimes a crack in the colour or a hole in the paint that reveals the linen, paper, or an underlying thinner colour. It functions as an entrance into the work. One could compare it to the eye or ear of a person. One of the feet in the painting Baby looks a bit rotten, which was necessary in order to make the painting alive.

I don’t believe an artist’s vision can totally differ from their life. How could it?

An artwork starts all the time. When I am executing an art piece itself, my goal is to be as blank as possible. It is difficult, and

a kind of meditation.

The moment when I feel that a work is perfect is crucial. The challenge then is to not try to improve the work even more, and consequently risk destroying perfection (from a painter’s point of view).

I am seeking a sinking sensation. It has to do with desire, to let go, to trust, for peace, or death.

A hole in the surface lets light in, and out, everything will change, transform.

Right now, light and darkness are everything. My question is can beauty also include cruelty? I don’t have time for irony, politics and external questions. I want to go straight to the core. Is it ugly? That is my interest – at the moment, there is nothing else.

Cecilia Edefalk, Baby, 1986–1987. Oil on linen, 230 x 432 cm (90½ x 170 in). Photograph by Carl-Henrik Tillberg.

On the night I was asked to be part of The Strangeness of Beauty project, I wrote a poem. Beauty can emerge in the night, just like now, in the day, at any time. Love is beauty – hatred the opposite. My aim, therefore, is to love more. My work allows that.

Do you want to know what I am doing? . . . How I do it?

Ask rather, do you know me?

If you do, my answer will flow out of me like running water

in the forest

in birdsong

in grouse in the mountains

the bow of a blade of grass

the glitter of the sun on the bay

the well of your eye

your scent

an ant crawling over a tree

everything that moves in nature without manipulation is love.

There you got the answer, this is how I know you.

You know this is the truth.

Cecilia Edefalk, The Meadow, 2013. Gelatin silver print on matte paper, 130 x 194 cm (51¼ x 76½ in).

Cecilia Edefalk, Dandelion Blue, 2020. Watercolour on paper, 56 x 37 cm (22 x 14½ in). Photograph courtesy of Norrköpings Konstmuseum.

Cecilia Edefalk, Gegenlicht, 2014. Gelatin silver print on matte paper. 36 x 54 cm (14¼ x 21¼ in).

Next Issue

The Strangeness of Beauty

Issue 10, 10 March 2021

Featuring a contribution by

Richard Deacon