¹

The Strangeness of Beauty – Issue 6 – Si On and Jakub Julian Ziółkowski

10-16 February 2021

View the full issue

Is Beauty Truth or is only Truth Beauty?

In ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’, written in 1819 by the English Romantic poet, John Keats, the final two lines read:

Beauty is truth, truth Beauty – that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

Yet soon after, other writers and philosophers were expressing very different opinions. For example, Friedrich Nietzsche, in his book The Will to Power, writes, It is disgraceful for a philosopher to say: the good and the beautiful are one. And by today, we have recognised that ugly can be just as true as beauty.

In a review of the book Why Beauty is Truth: A History of Symmetry by the mathematician Ian Stewart, the title of which refers to Keats’ words, Martin Gardner writes that T.S. Eliot called Keats’ lines meaningless, and that the renowned critic John Simon said in a film review that one of the greatest problems of art – perhaps the greatest – is that truth is not beauty, beauty not truth.¹ These poignant statements constitute some interesting grounds for discussion, and as we know many visual artists agree that although they put considerable emphasis on perfection in their work and the execution may be beautiful, a work’s content may not be pleasing to its audience. What John Keats meant in his statement is of course purely metaphysical. For him beauty is in the concept of its permanence, as he says in his poem ‘Endymion’, A thing of beauty is a joy forever.

In recent years much has been written about ugliness, and a number of art critics and writers have understood that there is a quality in ugliness that fascinates. While an excess of beauty does not seem to inspire or harness energy for discussion, ugliness creates ample grounds for debate. Another issue is that taste evolves. For example, research on the history of landscape paintings reveals that the same landscapes which have been revered since the mid-nineteenth century, had prior to that been objects of fear and anxiety. This is a clear indication that what is unfamiliar can often be considered ugly and unwelcome. The same is true within the urban environment. For example, much brutalist architecture of the 1960s, structures that for a long time were considered ugly are today listed buildings. With the passing of time comes greater familiarity, aesthetic sophistication, educational influences, and our tastes change. The discussion becomes ever more interesting as we focus on what it is that brings about such changes of mind.

Jakub Julian Ziółkowski, The Metamorphosis, 2020. Oil and mixed media on canvas, 46 x 55 x 10 cm (18 x 21¾ x 4 in). Courtesy the artist.

Jakub Julian Ziółkowski, The Metamorphosis, 2020. Oil and mixed media on canvas, 46 x 55 x 10 cm (18 x 21¾ x 4 in). Courtesy the artist.

Both Jakub Ziółkowski and Si On have placed in front of us some emotionally demanding works, which may reveal or question the life vision and experiences of each artist, even when we know them well. I know, for instance, that Si On is a woman endowed with a great joy of and appetite for life, and Jakub’s gentle nature, together with his kind and polite manner, give no hint of a person capable of unnerving one’s feelings. We can ask ourselves what such disturbing images as theirs can have to do with their personal emotions? Could someone’s outwardly strong and tangible expressions be matched by the power of their inner feelings? How do emotions held deep within a person’s brain and heart interact?

I met Jakub some years ago and subsequently visited him in Kraków prior to his solo exhibition at Parasol unit in 2011. To better understand his artistic ideas and thought processes, I asked if we could visit the small town of Zamosc, where he had been born and raised. We undertook the half-day drive on some winding roads, which at the time was the only way to reach it. The visit was a unique experience, and I was fascinated to hear about Jakub’s childhood and the considerable freedom he had experienced during the early years of his life, when he was able to roam alone around the town for countless hours on his bicycle. At home, Jakub’s imagination was likely fed further by other fascinating oddities, as both his parents were medical doctors. There were probably plenty of medical books and journals around the house, which would have given him generous access to depictions of all the systems of the human anatomy.

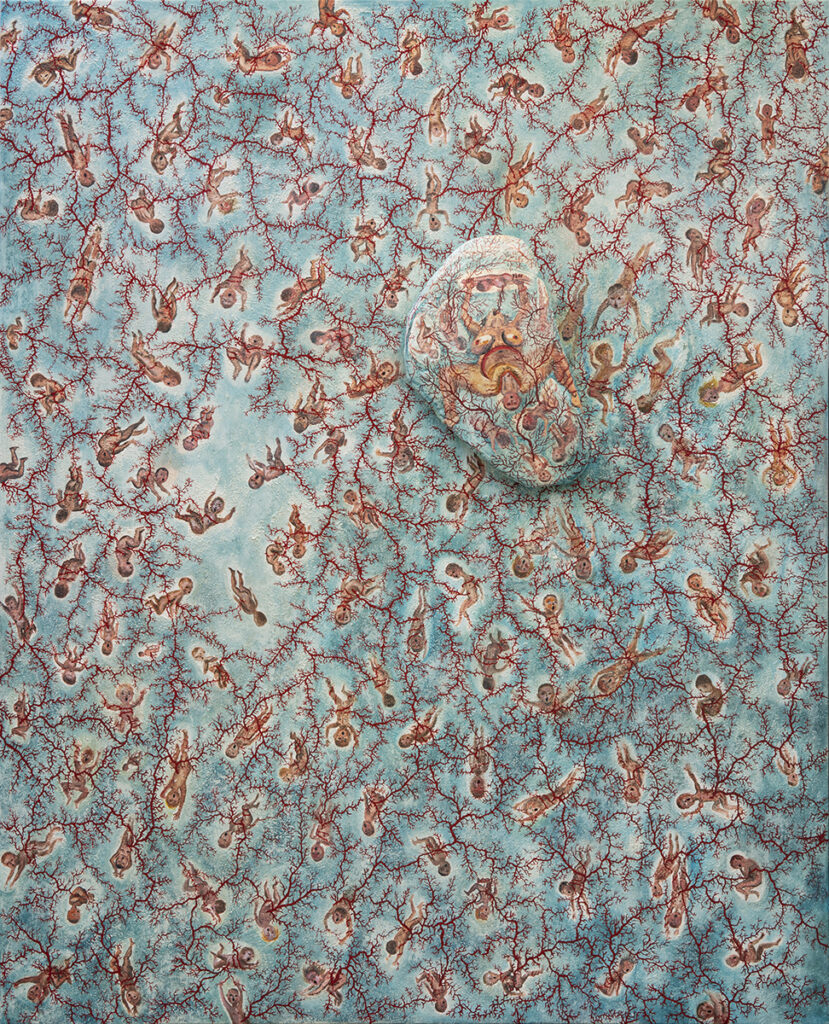

Jakub Julian Ziółkowski, The Endless Beginning, 2020. Oil and mixed media on canvas, 210 x 170 cm (82¾ x 67 in). Courtesy the artist.

Zamosc itself was built between 1579 and 1618, based on the utopian model of an Italian Renaissance city. The town’s concept was to encourage acceptance of all faiths in a place where life could be lived in harmony. From today’s standpoint, it seems horrific that such a utopian environment could have become host to a concentration camp during World War II, and its fortress used as a depository for human remains. What could a child make out of all that? What could an imaginative youngster and, later, a young painter have made of such experiences? Now that our planet has lived almost a full year with the devastations of the Covid-19 pandemic and the heart-breaking images that appear in the media every single day, how should we understand and imagine the concept of beauty? In each of us, artist or otherwise, there is compassion, empathy, sorrow and regret, but being human is also and above all about life and the future.

I confess that Jakub’s images here fill me with incredible emotions. Lost in my own thoughts and forgetting who I am, I engage my mind’s eye with these images, trusting my human instinct to react. What I see is that life is fragile, unpredictable, and precious, and we need to rescue it, whatever the cost. Like many of you, I love life, and although these images seem unnerving to me, there is also a coy and tender quality to them, which hints at a light somewhere, albeit at a remote distance.

Jakub Julian Ziółkowski, The Inward Descent, 2019. Oil on canvas, 150 x 130 cm (59 x 51 in). Courtesy the artist.

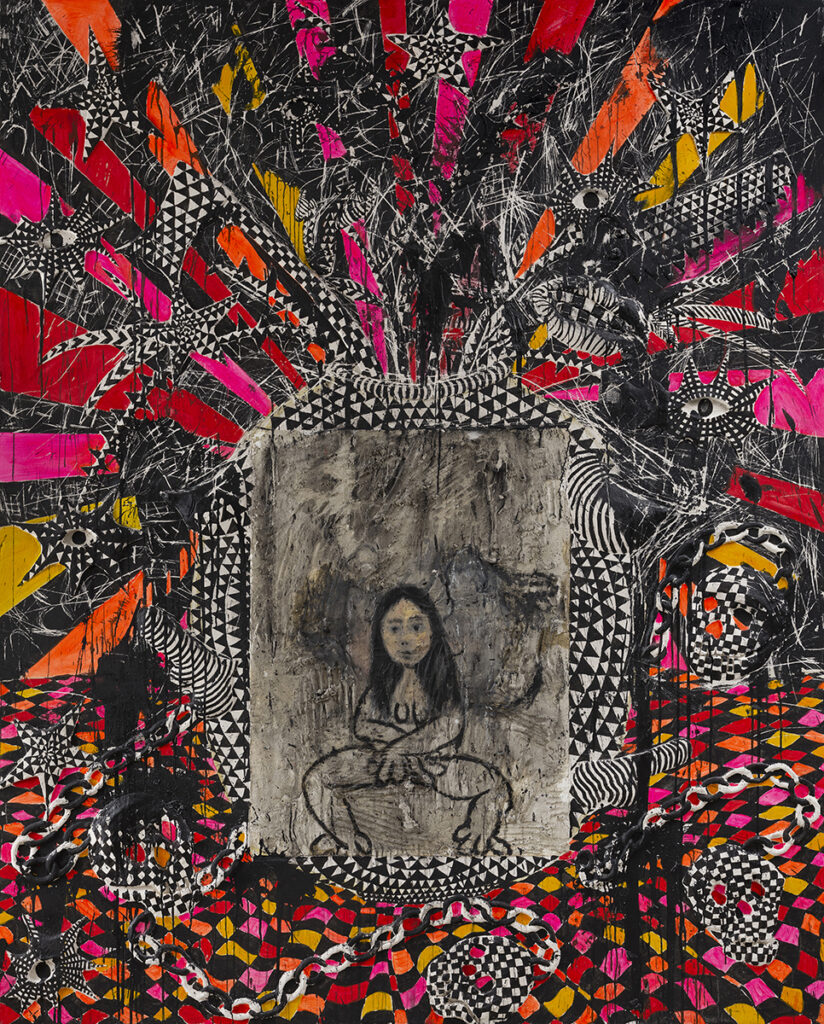

Jakub and Si On’s paintings feed into one another, with Jakub’s paintings often highlighting the dark side of humanity, while Si On’s works, even though intense, do not disguise her sense of humour and fun-loving nature or perhaps her Weltanschauung (worldview). For all her works, Si On borrows freely from any media and any topic, and indeed this lack of inhibition is a hallmark of her creativity and allows her to make any subject her own. Si On’s fatalistic thinking, even while dealing with the most desperate of subjects, ensures that one never feels sad or sorry for the human beings she depicts, because the artist’s inherent optimism tells us they can always get out of whatever dead-end they are in.

Having been born and educated in South Korea, much has been said about the shamanistic influence in her artistic practice and the later Japanese influence while she was studying in Kyoto, but increasingly with time, and having gained confidence in her artistic work, Si On selects and develops her own artistic language and vocabulary.

Faced with a wealth of possibilities and encountering numerous artistic languages during my professional activities, I slowly realise that beauty is an abundance of many things, nevertheless I ask myself what beauty really is, and whether an artwork has to be beautiful and, if so, for whom?

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director

1 Martin Gardner, in ‘Is Beauty Truth and Truth Beauty?’, Scientific American, 1 April 2007, discusses Ian Stewart, Why Beauty is Truth: A History of Symmetry, Basic Books, 2007.

Si On

The Strangeness of Beauty

Si On, That’s Cruel, That’s Okay, 2020. Mixed media on canvas, 182.5 x 153 x 8 cm (71¾ x 60¼ x 3¼ in). Courtesy the artist.

During my work process, when I am lucky enough, I get to travel the past, see the world even before I was born and the future, have empathy for others, separate my emotions from my body, become a man and a woman, neither a man nor a woman, a child and an old person, neither young nor old, be sad and happy, fearful and peaceful, painful and cured, confess my mistakes and forgive them, hate and understand, give up and get up again.

Just like where there’s a start, there must be an end, where there’s life, there must be death, and where there’s light, there must be shadow, we live and coexist with all the opposites. That’s why it’s natural that we live being conscious of opposite things. It is painful sometimes but at the same time it is also very beautiful.

Si On, Be Where You Are, 2020. Mixed media, 182 x 55 x 44 cm (71¾ x 21¾ x 17¼ in). Courtesy the artist.

During this process I enter an indescribably strange state. And that is what I call beauty. I am possessed of this feeling for beauty, that state of mind. And because of that awareness, I get the courage to take risks, ready to be sacrificed, no matter that I am wounded and destroyed, I can keep going back for the beauty.

Si On, Wise Woman, 2020. Mixed media mortal on panel, 240 x 200 cm (94½ x 78¾ in). Courtesy the artist.

Next Issue

The Strangeness of Beauty

Issue 7, 17 February 2021

Featuring a contribution by

Carla Arocha & Stéphane Schraenen