The Strangeness of Beauty – Issue 4 – Luca Berta and Francesca Giubilei

27 January - 2 February 2021

View the full issue

The Pull of the Kitsch

In October 1986, the New York art world got itself in thrall to a massive polemic that brought into opposition several respected art world personalities. The issue in this commotion was the exhibition 4 Young East Villagers at the established Sonnabend Gallery in Soho. Ashley Bickerton, Peter Halley, Jeff Koons and Meyer Vaisman, whose works were in this exhibition, were four young artists between 26 and 33 years old, living and working in East Village, though without forming any artist collective or movement. What these young men had in common was an awareness of how society was, once more, about to change. This time, it was heading towards excessive materialism and greed fuelled possibly by the spirit of Wall Street and a strange urge in society to reach fame and stardom at any price and within the shortest possible time span. Living in New York City myself during this period and realising the coalescing changes that were about to happen, I could not have agreed more with these artists. What was remarkable though was how one of them, Jeff Koons, supposedly a successful stockbroker on Wall Street and prior to that a gifted membership seller at the Museum of Modern Art, was going to play a decisive role as the agent of change in this process. In the past, there had of course been other agents of change, such as Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, and society as a whole, including the intelligentsia, somehow absorbed the new tendencies.

In the 1980s, almost everything in New York was inflated and the art world being somewhat uneasy was anticipating something even more radical than the Neo-expressionist painting of the early 80s. These four young artists, and Jeff Koons in particular, were on the spot to provide a whole new vocabulary in art as it responded to the mood of the time – the adoration of kitsch and banality, which was also gorgeous, enticing, and irresistible. Koons’ works were colourful, shiny and large-scale inflated animals, a gloriously golden ceramic sculpture of Michael Jackson, glamorous love-making scenes portraying Koons and his bride Cicciolina, Spalding basketballs mysteriously afloat at total equilibrium in water tanks, and eventually his gigantic puppies covered in growing plants and flowers – positioned outside museums and art events, these living sculptures left no one untouched, charmed and/or disarmed. Thus, his career was made, and no powerful art collector could do other than own at least one or several artworks by Jeff Koons. For regular museum goers and those who could not afford a Jeff Koons, there was nothing else to do, whenever they saw a work of art by Koons, but to utter the word ‘beautiful’.

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director

Parasol unit foundation for contemporary art

Jeff Koons, Puppy, 1992. Stainless steel, soil, geotextile fabric, internal irrigation system, and live flowering plants. 1240 x 1240 x 820 cm (488¼ x 488¼ x 322¾ in). Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa.

© Jeff Koons. Image source: Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa. © FMGB Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa. Photograph by Erika Barahona Ede.

Luca Berta and Francesca Giubilei

The Winding Alley Between Kitsch and Paradise

Having to draw up a ranking of the objects that best embody the notion of kitsch, the first place would be easily won by the plastic gondola souvenir, even better if kept and displayed at home in its original packaging. A plastic gondola on the mantlepiece recapitulates a world, an aesthetic, a way of conceiving personal experiences. Yet gondolas, if you look closely, are eleven-metre-long black blades that cut through the water in silence, manoeuvred by a single oarsman – perhaps more like Charon’s infernal ferry than a toy.

Goethe recounts, in his memoirs of a trip to Italy, that his father owned a model of a gondola, with which on rare occasions he was allowed to play. For this reason, on his first arrival in Venice, the features of the boat seemed familiar to him. Already in its time, Venice was the place of the déjà vu of beauty. The history of kitsch had yet to begin, but in a way it has its roots in the romantic poetics that Goethe helped to found. The concept of the sublime projects an aesthetic space alternative to that of beauty intended as a fulfilling, harmonious coincidence with the expectation of the subject in a contemplative position. The sublime overwhelms the subject, exposes them to uncontrollable otherness, crosses them, makes what is strange/extraneous break into an exceptional aesthetic experience. But this exceptionality soon intersected with the nascent bourgeois society and with the new habits of cultural consumption. The feeling of infinity swiftly translated into sentimentality. The genius in a melancholy pose. Kitsch normalises the sublime by bringing beauty back into controllable, reproducible, that is, also saleable paradigms (just as an international and markedly bourgeois decorative style, such as Art Nouveau, is affirmed). The traumatic dimension of romantic beauty is anaesthetised, miniaturised – what Baudelaire called the ‘toy style’.

This mechanism underwent a further evolution during the twentieth century. Kitsch continued to act as a catalyst for large-scale cultural phenomena, hastening the decline of modernism and deeply innervating Pop Art and the postmodern. Contemporary art is an arena without a definable perimeter, in which convective motions and interferences no longer admit a univocal historical reading. However, all artists must deal with a phenomenon – since the mid-twentieth century, art has lost its monopoly on aesthetics. The design and production of beauty have proliferated in the new territories opened up by the advent of mass culture and consumption: advertising, industrial design, interior design, fashion, the mass media. A widespread aestheticisation has enveloped every dimension of individual and social existence. This process has made the ground far more slippery for the artists, who often felt called to formulate theoretical positions capable of distinguishing their practice in this pulverisation scenario.

Mass tourism is another of the implications of this trend. Venice, as we know, is one of the symbolic places of mass tourism par excellence. The mutation that has taken place in the aesthetic experience in general seems to have changed the beauty of the city itself. Venice is a sort of capital of widespread aesthetics, of beauty that pervades every perception, every glimpse, every step, every experience. Not necessarily, however, a clean and glossy beauty. Here then is the poetic peeling wall next to the Gothic three-light window, the bell tower and the cloudy sky reflected in a puddle as soon as the storm ends, Titian’s altarpiece, spritz glasses on a table by the canal, the tuft of seaweed on the bricola (mooring poles) – all shots just a click away from being miniaturised on our screens and distributed in everyone’s online shop window.

Photograph by Martina Pizzoferrato.

Venice is incontrovertibly beautiful. But its beauty seems to have lost the element of strangeness/extraneousness, or at least it seems to have hidden it to offer at first glance only the immediately available side of what is beautiful. Venice is a symbol of widespread aestheticisation, and at the same time one of the crucial hubs of contemporary art. One wonders if there is not a constitutive link between these two phenomena. As if the city somehow nailed today’s artists to a scenario in which the weight of the past and the oppressive presence of a tirelessly aesthetic work leave extraordinarily little room for manoeuvre. In an era when aesthetics is often a glaze that covers everything, the frontier on which artists work to articulate beauty, otherness and meaning becomes increasingly difficult to place. Venice, in this sense, leaves no exit strategy, it does not fool you into finding easy ways out. The roads, here, are never straight.

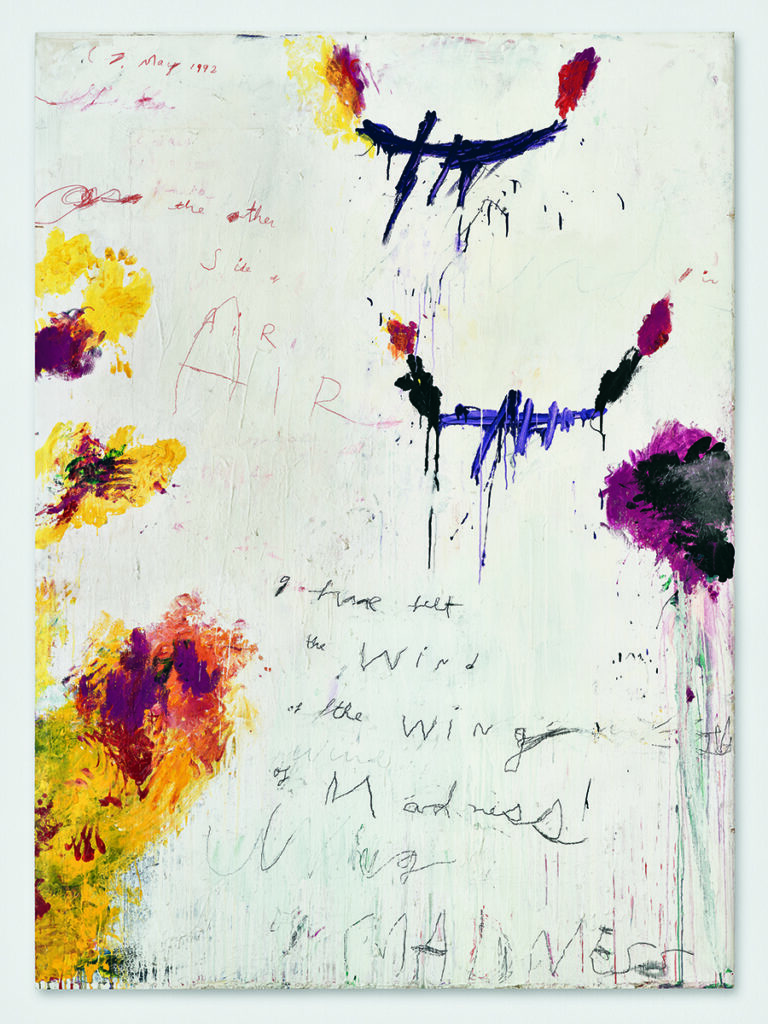

In 2015, the Ca’ Pesaro museum in Venice presented Paradise, a powerful retrospective of works by Cy Twombly (1928–2011). Four years had passed since the death of the artist, who in 2001 was awarded the Golden Lion at the Biennale for his famous Lepanto Cycle. On the off-white background of one of the works on display, Untitled, 1992, there were some fragmented sentences, such as ‘On the other side of AIR’, and ‘I have felt the wind of the wings of madness’ (Baudelaire), scratched into the pictorial matter. Along the lateral margins appeared patches of yellow, red, orange, and purple paint, spread with the fingers. At the top right, two thin black-blue crescents, spread out in white. Two gondolas? At the bow and stern some red plumes – like flames that burn in a dazzling, desperate lagoon, illuminating and destroying. ‘Beautiful’ was the one thing we said when leaving the room.

Cy Twombly, Untitled, 1992. Acrylic, oil paint [paint stick], coloured pencil, lead pencil on wooden panel.

235 x 172.2 cm (92½ x 67¾ in). Collection Cy Twombly Foundation © Cy Twombly Foundation.

Photograph by Stefan Altenburger.

Next Issue

The Strangeness of Beauty

Issue 5, 3 February 2021

Featuring a contribution by

Katy Moran