Learning to Look with all Our Senses

Among the profusion of information, guidance and comments we continue to receive during the Covid-19 pandemic some are helpful, some are really good and others are just great. Whether or not within the next few months we can revert to where we stood in our life prior to the pandemic, one thing is certain, the current change and pace of life that we have submitted to will have a lasting effect on our senses, bodies and minds.

To protect their citizens, some countries closed their borders, others restricted movement altogether by excluding travel both within their own or to a foreign country. As a result, frequent travelling has for now become an activity of yesteryear. Fortunately, we human beings are flexible enough to adapt to new circumstances and, thanks to technology, have been able to communicate on many levels with the outside world. ‘Social distancing’ implies that touching people in public is to be avoided and that, after all, can perhaps be seen as a welcome restriction. Prior to the lockdown, being bumped into, by other people’s backpacks, shopping bags or even their limbs, was an everyday part of life. I recall the frustration of being hit right and left in aeroplanes or simply on the street and looking back with nostalgia to those days when it was considered disrespectful to come into physical contact with other people in public places.

Another welcome life experience is having relearned to be in touch with one’s surroundings. I am not altogether sure what has contributed to this change of attitude. Is it the necessity of being on the lookout for potential danger and being cautious before acting or is it simply due to having more time to consider options as opposed to acting on necessarily hasty decisions? For myself, I am glad to have this time.

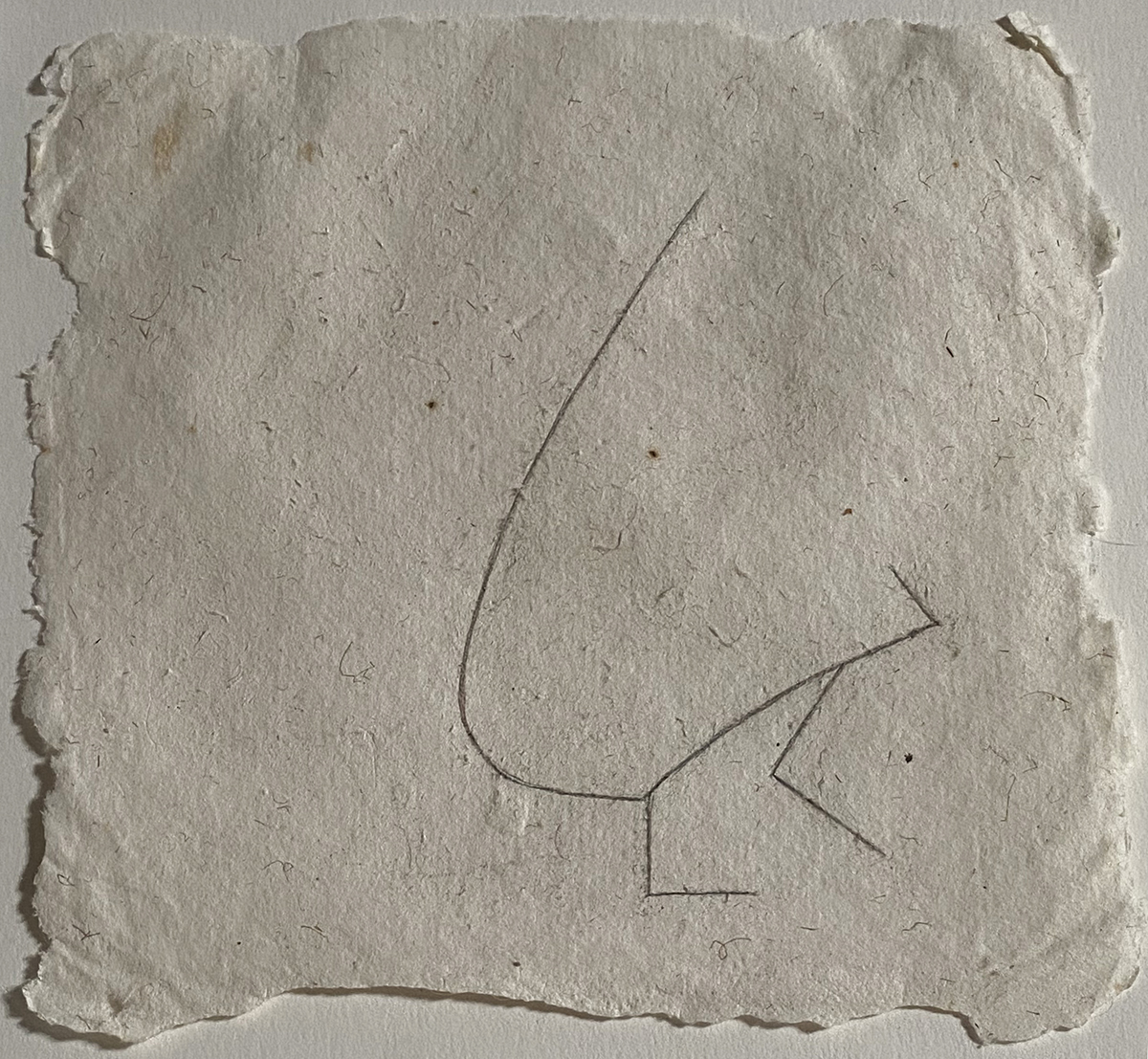

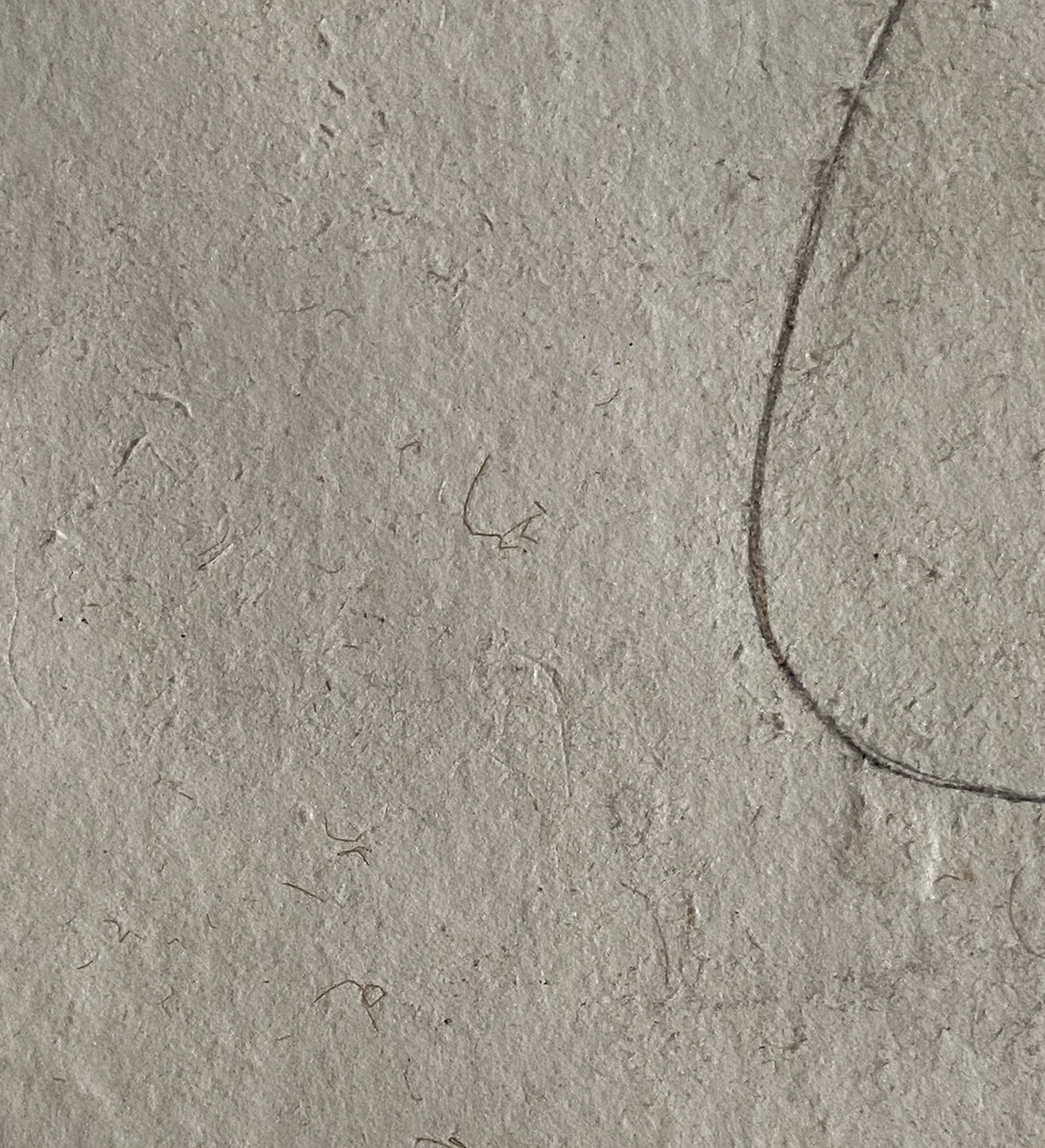

Let’s keep in mind this renewed enjoyment of looking carefully at things but go back to our artistic discussion and examine some examples of how artists have looked or are still looking at their surroundings. Sometime in the early 1980s during one of my usual gallery visits, I came face to face with a cast bronze sculpture that looked like the outline of a cat. It was an intriguing object, something like a drawing in the space. My interest grew considerably when the artist Joel Fisher explained his work to me and the process through which this Untitled sculpture had come about. Fisher used to handmake paper, a process which in itself requires patience and a love of creating. He would place the paper to dry on some rough felt he had in his studio and, not surprisingly, some felt fibres would inevitably adhere to it.

On close examination of the paper’s surface, Fisher discovered that some of the felt fibres had interesting shapes, which was enough to incite him to further his exploration of a new body of works. Fisher first identified which of the felt fibres interested him, then with a pencil he would draw their shape at a larger scale and in close proximity to the fibre. This intriguing practice allowed Fisher to create a sizeable series of works on paper which would never have come into existence were it not for his keen interest in looking intently at those paper surfaces.

Later, he ventured to make sculpture by turning some of the two-dimensional drawings into three-dimensional works and this is how his Untitled work had been realised. Naturally, I was amazed by this elaborate process and exercise in perseverance and patience. In the 1980s, such a practice seemed special but could have happened, but in subsequent decades such artistic mindsets have become increasingly rare among artists. However, with the current lockdown we are all experiencing, it has once more become a welcome practice to take time to gaze with our eyes and to think more consciously with our minds.

Among the numerous contributions I have had the good fortune to receive from artists in response to the O Sole Mio project, I realise that many of them put considerable importance on the act of gazing, on scanning their surroundings, and on the careful observation of minute details. Not surprisingly, they found that the process had markedly heightened their sense of perception. The four contributions I took pleasure in selecting for this sixth issue of O Sole Mio, which considers the theme of learning to look with all our senses, include works by three artists, Richard Wentworth, Koushna Navabi and Ruth Whaley, and a reflection by Lekha Poddar, an art collector and founder of the Devi Art Foundation in New Delhi. During this time of required isolation, she sees in an artwork parallels with the inspiration to be found in the iconic song ‘O Sole Mio’. Each of these contributions focuses differently on the act and the art of gazing intently and it is certainly enlivening not only to discover their thoughts and their art but also my pleasure to thank them profusely for having created such thought-provoking works for the project.

A leading figure in British Sculpture and a proponent of the New British Sculpture movement of the 1980s, Richard Wentworth is a conceptual artist whose work and ideas have had considerable influence on younger generations of artists, often encouraging them to explore chance and coincidence in their work.

A special characteristic of Wentworth’s work is its seemingly practical nature, whereas the work itself is the result of considerable thought and deliberation. It is therefore not surprising that for his contribution to O Sole Mio he has presented a work which incorporates, as he says, ‘fleeting stuff’ in a ‘chipped glass prism’. How marvellous indeed to encapsulate in one minuscule object, endless hours of reflection.

‘I Shall Salute the Sun Once More’ is the title of a translation by the artist Koushna Navabi of a well-known poem by one of Iran’s foremost modern poets, Forugh Farrokhzad. The poem is commonly translated into English as ‘I Will Greet the Sun Again’. In this special work, Navabi connects with the deceased poet on a personal level, which could be seen as a homage to Farrokhzad, but could also signal Navabi’s interest in engaging intellectually with this singularly daring and innovative female poet whose untimely death at the age of 32, in 1967, left the Tehran intelligentsia short of many insights and inspirations.

Here, the impulsive freedom of modern poetry is juxtaposed pictorially with various sections of a very tall tree which now exists only in an uprooted state on the ground. In its current condition, the fallen tree is photographed by Navabi from an angle that accentuates its length. By definition, an uprooted tree lies somewhere between life and death, or without having any defined attribute or vertical territory. The two works here, one by Farrokhzad in written language and the other in pictorial language by Navabi, express complementary concerns. Together, they speak vividly of the intense inner feelings of both these women. Farrokhzad’s daring yet poetic exploration finds a kindred spirit in Navabi’s highly loaded imagery. Ruth Whaley’s intimate painting The Gaze has two distinct parts, an angel and a freshly blooming rose, both hugely symbolic. The figure of the angel was inspired and copied after a large wall painting at Santa Felicita, entitled Annunciation (The Virgin Mary), 1528, by Pontormo. With The Gaze, Whaley plays conceptually on several layers of thought. The wall painting at Santa Felicita not only takes us to another era, but the Archangel Gabriel’s intense gaze at the Virgin Mary bears good news and heralds hope for a bright future. By taking us this far back in time, Whaley also gently reminds us that hope has always been alive in the human mind.

From another part of the world, in India, Lekha Poddar offers her reflection on the confinement we are all currently experiencing, no matter where we live on planet Earth, and our potential faith and hope in a future recovery. Harnessing the power of creativity and art, Poddar presents a work by Iqra Tanveer entitled Paradise of Paradox, which like all other works in this issue is about seeing and discovering hope.

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director