Imagining the Sun

Within the context of the O Sole Mio digital exhibition during this period of Covid-19 lockdown, and thanks to the many artistic and intellectual contributions, we are discovering ever more about the many representations and meanings embodied by the sun. The first two online issues explored the importance of the sun, light, hope, love and optimism as embedded in the iconic song ‘O Sole Mio’. All these attitudes help us to overcome the fear and pain of the coronavirus and to work towards a better future. However, in subsequent issues we had to face up to the less positive and undesirable aspects of the pandemic: shock, fear, the importance of recognising early signs of danger and, finally, the need to reflect on what has led us into today’s outrageously dramatic reality. Next, we oriented our attention towards examining our own physical and mental states of mind and being during isolation, as well as considering how they have been affected and are evolving over time. For example, after having digested countless reports and images of devastating situations around the world and our own confinement, we may have reflected deeply on what it means when we talk about the human condition. We may have placed the whole emphasis on our senses, those incredibly important human faculties that many of us have neglected during the busy years prior to Covid-19. Issue 06, for example, discusses our heightened sense of perception when an unseen danger brings us face to face with the reality of who and what we are. But, do our senses lead us towards truth? Much of the truth in life, according to the Greek philosopher Plato, can be reached through philosophical reasoning, as demonstrated in his ‘Allegory of the Cave’ in which prisoners see as a physical reality the shadows cast by the sun or a fire.

Throughout our lives we have taken it for granted that the sun exists as part of the universe’s inventory. Along with its many actual functions, for we humans the sun also represents joy, warmth and happiness. Indeed, after cold or stormy weather, we particularly appreciate a sunny day, which is precisely the subject of the song ‘O Sole Mio’. But do we fully realise the roles and the importance of the sun? Is it a coincidence that all of Europe has basked in warm and sunny days during the period of lockdown? We hear, of course, that this particularly clement weather heralds a hot, dry and inclement summer in which, while living with Covid-19, we will surely face a vivid and heated discussion about the unresolved warming of our climate.

Like many others, I have attempted to understand the many roles played by the sun. Whenever we hear this short word of just three letters, an image of it inevitably springs to mind and our other senses come to life. We see, we hear, we smell, and we recall our taste and tactile experience of earlier events. True, a sunny day is a joyous concept in this world, but in reality it is much more than that. Thanks to the Covid-19 lockdown, this meaningful project and the numerous innovative contributions it has generated, I have learned to recognise and appreciate a wider range of meanings attributed to the sun and how vital they are in all our lives. Therefore, several future issues of O Sole Mio will attempt to unravel the many meanings of the word, its image, concept, and so many of its other roles. As powerful as the word ‘sun’ is, it is also crucial to understand its importance.

For most of us the appearance of the sun and light are a joyous occurrence, but for others they might unleash existential considerations, such as the distinction between reality and illusion, as they did for Plato’s prisoners in the cave. Al-Ludra / A Pocket Star, Darren Almond’s exquisite video of the sun, is not only an astute observation and interpretation of the blazing star, it is also a great starting point for this conversation. In his brief video, a glowing orb hovers within dark space. Seduced by its purity, simplicity and reductiveness, I am utterly thrilled to look at it on my handheld device. It is indeed a beautiful image that can appear and disappear with ease. In many ways, I have taken it as a welcome gift, particularly at a time when the sheer fact of our existence hangs on little more than a thin thread. In its purity and simplicity, Al-Ludra / A Pocket Star stands out beyond anything we could imagine. We could look at it, enjoy it, and go about our lives. Or we could take another approach and take it as a starting point for some critical learning and reflection. I encourage us to do the latter.

In my initial conversation with Darren Almond about his Al-Ludra / A Pocket Star, he gracefully stated, ‘I think it fits rather beautifully with the title of your digital exhibition. I also really like how the footage migrates from my hand to yours as you watch it on your phone, reaffirming our collective communion with our closest star.’ It meant a great deal to me to grasp Almond’s state of mind. Particularly in these challenging times, the sun in this delicate work stands for and informs our collective solidarity. Indeed, as soon as we play this brief video of the sun on the screen of our own device, it takes on its own dynamic by seeming to float in an undefined space, which in turn empowers our imagination. How magical and surreal it is to think that while there is only one sun in our solar system, any one of us can hold it in the palm of our hand, and that on a device which, ironically, over the past two decades has become a unifying element in the lives of most people.

Shezad Dawood’s imagination could author an endless number of science fiction stories and be the steadfast protagonist in every single one of them. Sunspots is a revealing video work undertaken in collaboration with his sister and brother, Samya and Mikayl Dawood, during the Covid-19 lockdown in London. In analysing the concept of the sun, Shezad Dawood calls on the works of a number of contemporary fiction writers as well as one of the greatest philosophers in human history, Plato, in order to examine truth, but also the boundaries between the human condition and senses, which do not always reveal the truth.

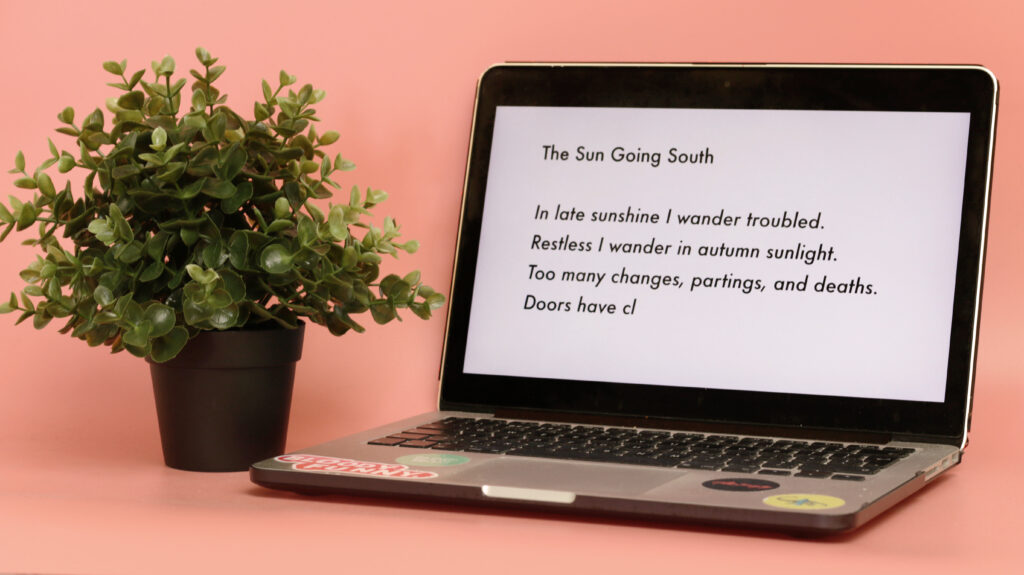

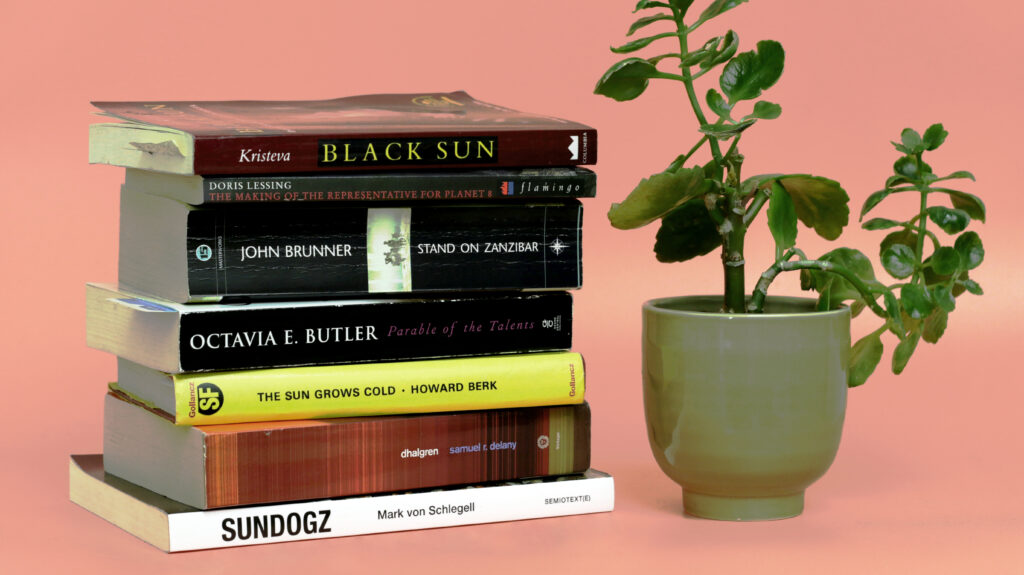

In Dawood’s carefully staged and orchestrated installation, a succession of intriguing images, in which an open laptop bearing various texts and images is juxtaposed with evergreen houseplants in different types of pot, and a number of books whose authors have seemingly influenced Dawood. The peach colour of the background may accentuate the domesticity of an otherwise uncanny setting. Revealingly, Dawood’s use of ‘The Sun Going South’, a poem by Ursula K. Le Guin, strangely echoes not only the situation in Plato’s cave but also the restricted conditions of our life today. Le Guin’s mere use of the word ‘sun’ has the power to generate a multitude of images in our mind. They in turn can engender profound feelings which hopefully prompt us to look more deeply into what they mean. Dawood assuredly reaches some enlightening thoughts, as in the text accompanying his images he references Plato’s cave, a concept that directs us to distinguish the difference between reality and illusion, to disentangle any confusion for which our senses are the culprits.

In her paintings Ana Elisa Egreja, too, manifests an intriguing vision of the sun, which causes confusion between reality and illusion. The output of Egreja’s imagination can seem nostalgic or even uncanny, particularly in the way she employs light to create visual tension between illusion and reality. Whether her paintings depict the quaint domestic environment of some bygone era, describe the treasured memories of a former family home, or record a vacated building destined for imminent destruction, they each have an energy capable of harnessing sensory feelings and subsequently authoring an unusual and uncanny atmosphere, as for example in Canto da poça, 2017, which ironically was painted three years before the Covid-19 lockdown. Egreja is one of a number of painters whose vision is very much in tune with the realities of our time. They do entertain, but above all they prompt us to think and question. As in the allegory of Plato’s cave, the realities painted in Egreja’s works are only the tip of an iceberg – a greater truth it seems is submerged in the water.

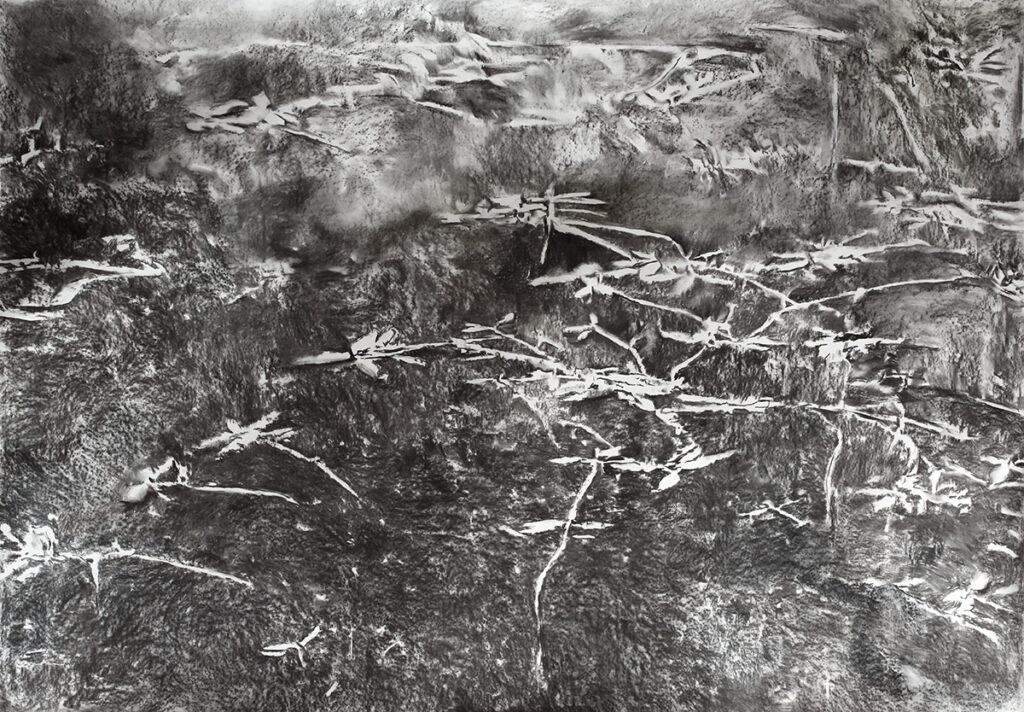

While imagining the sun, Ana Gallardo sees it, above all, in relation to the land and water, because together these three generate growth and renewal. Gallardo’s vision in these challenging times remains, therefore, hopefully and optimistically focused on the natural world. Recognising the flexibility of the medium of drawing, Gallardo indulges in creating elaborate and often large-scale drawings in which renewal of life is the quintessential protagonist.

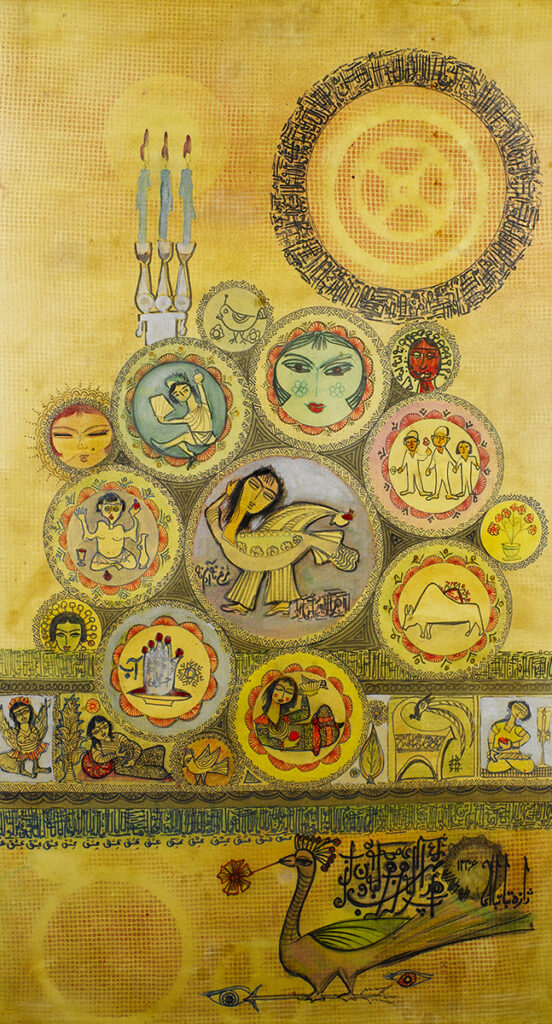

In the reflection section of this issue, Iranian-born scholar of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Iranian art, Layla Diba provides some enticing images and insightful background to a totally different culture. The Khorshid Khanum (Maiden Sun) is one of the most enduring images in the history and culture of Iran, which has traditionally venerated images of femininity. Apparently, images of the sun first appeared connected to the cult of the divinity Mitra in the first century ce, while the image of the Maiden Sun has evolved over time. Diba’s research has brought us a 1957 reincarnation of that with a profusion of idealised modern images, painted by Jazeh Tabatabai (1931–2008). A member of the Saqqakhaneh movement, named after the water fountains that are at the heart of any traditional coffee or tea house, Tabatabai, like other Saqqakhaneh artists, created a visual language that in the main depicted genre images from Iranian cultural artefacts. In his fantasised representations of the sun and idealised women, Tabatabai’s thoughts hover between the reality and illusion of his sensory feelings. How would they respond to the truth?

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director