The Sun as Emissary to Discover Analogies

As we saw in Sonny Sanjay Vadgama’s work, Our Blood That Flows, featured in issue 09 of the O Sole Mio digital exhibition, the sun and the path it appears to take across the sky from sunrise to sunset can give some of the most vibrant performances. Having also seen other artworks destined for this project, in which the sun could easily have been the leading player, I have learned something interesting. Yet again, it has confirmed why photographers usually prefer to work on cloudy days. However, here and for the sake of this introductory essay, we are considering the sun as an emissary or a vehicle that allows us to discover reality and explore its analogies – those other attributes that any object could possess. They could be physical, but equally associative meanings or even something like metaphor, which in turn offer us a myriad possibilities. I find the concept of facing such a wealth of possibility utterly exhilarating, particularly during this period of Covid-19 isolation. In the same breadth of thinking, this paradox might explain why technology has become such an important tool for communication during the pandemic.

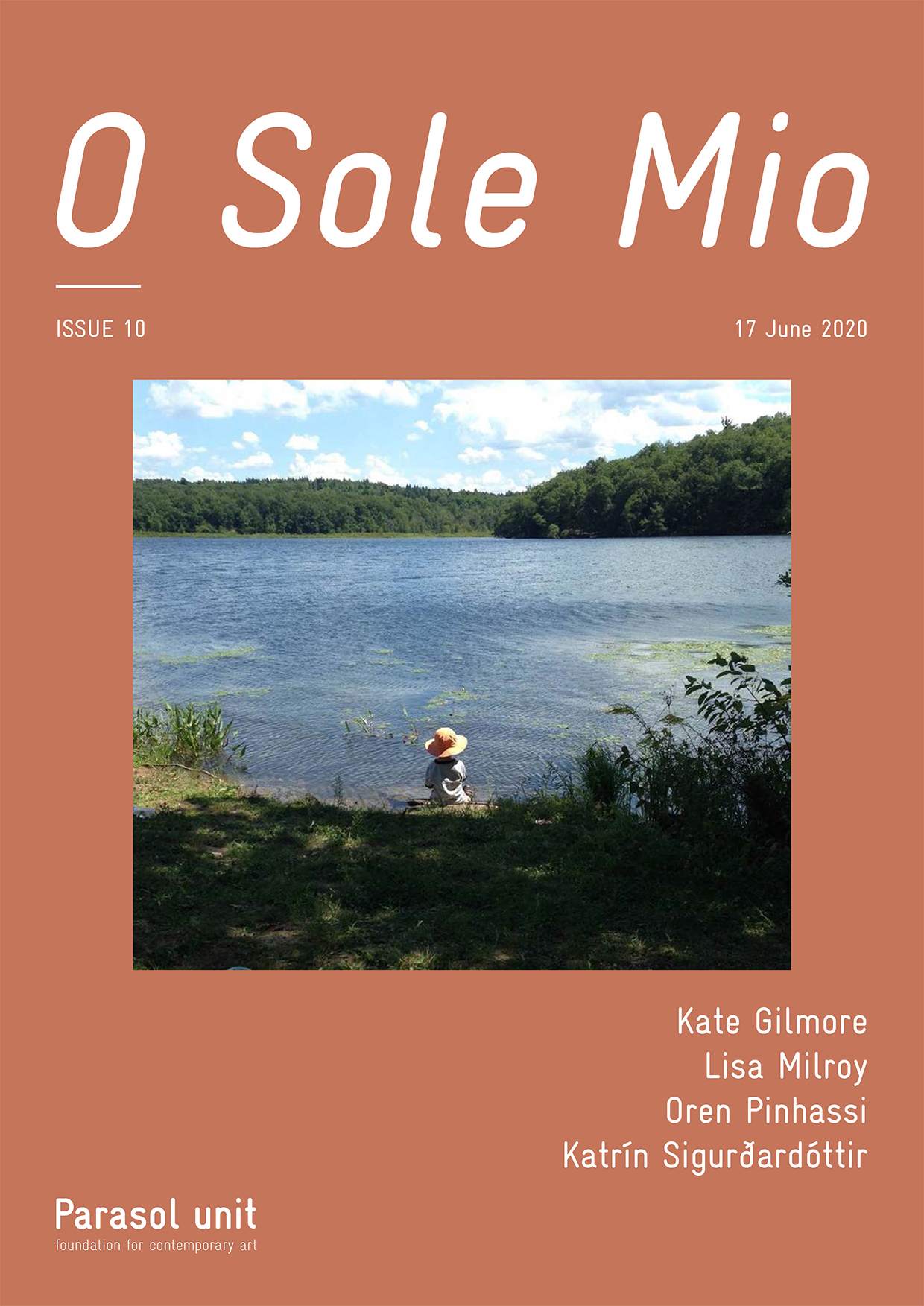

All the artists we have brought together in this tenth issue of O Sole Mio seem to be interested in finding analogies within the realities they present in their work, even for example in the apparently simple photograph, entitled Eli, by American artist Kate Gilmore. The photograph shows a small child seated on the shore of a lake, peacefully looking at the gorgeous and serene scenery on a totally calm, sunny day. It is a lovely and captivating photograph, but is it really all that simple? Thinking further, it is easy to realise that in these uncertain times with the threat of Covid-19 still hanging over us and now, too, the escalating race protests, this delightful image may have greater significance than at first appears. By now, many of our readers will have associated it with a nineteenth-century style of painting known as Romanticism. The German artist Caspar David Friedrich and American painters such as Fitz Hugh Lane and Martin Johnson Heade come to mind. In such paintings, a majestic view of nature occupies almost the entire canvas in contrast to a minuscule back view of a lone person positioned somewhere in the foreground. These paintings remind us of nature’s awe-inspiring importance and power, just as the current pandemic makes it clear that despite all of humanity’s advances, nature remains very much in control.

All the artists we have brought together in this tenth issue of O Sole Mio seem to be interested in finding analogies within the realities they present in their work, even for example in the apparently simple photograph, entitled Eli, by American artist Kate Gilmore. The photograph shows a small child seated on the shore of a lake, peacefully looking at the gorgeous and serene scenery on a totally calm, sunny day. It is a lovely and captivating photograph, but is it really all that simple? Thinking further, it is easy to realise that in these uncertain times with the threat of Covid-19 still hanging over us and now, too, the escalating race protests, this delightful image may have greater significance than at first appears. By now, many of our readers will have associated it with a nineteenth-century style of painting known as Romanticism. The German artist Caspar David Friedrich and American painters such as Fitz Hugh Lane and Martin Johnson Heade come to mind. In such paintings, a majestic view of nature occupies almost the entire canvas in contrast to a minuscule back view of a lone person positioned somewhere in the foreground. These paintings remind us of nature’s awe-inspiring importance and power, just as the current pandemic makes it clear that despite all of humanity’s advances, nature remains very much in control.

Oren Pinhassi, in his sculpture Standing Figure, focuses on the dichotomy between our human ability to be inspired by the real sun/natural light, and our capacity to sink ever deeper into the underworld of technology. Not unlike the artist David Claerbout, yet totally differently, both artists question such life concepts, alerting us and making us aware of the danger of allowing ourselves to become completely absorbed by our computers, smartphones and other such technological devices. Understandably, during the current pandemic they have all become vehicles of our hope to communicate with the outside world.

But the concerns of these artists go much further. In Pinhassi’s Standing Figure sculpture, a pane of glass represents the void which seemingly forms the head of the figure. Generally, a sculptured head has a certain volume, but here it is a void with a flat outline and the glass pane simply reflects images it receives from the outside world, without any ability to think, interpret or make decisions. Standing Figure is Pinhassi’s response to the human condition of contemporary beings in this era of technology and his own isolation. Thinking back some sixty years, we could revisit Alberto Giacometti’s impressive and emaciated walking figures. Made of course in a totally different time and environment, they were his reflections on the human condition of modern man. Although the 1960s are often referred to as a time of extraordinary possibilities and human aspirations for communication that included even travelling to the moon, the anticipation of a great artist, such as Giacometti, warned of a disturbing future.

Like Pinhassi, Katrín Sigurðardóttir lives and works in New York City. At the height of the pandemic, when going outside was limited, Sigurðardóttir took a daily walk from her studio to an area near the Statue of Liberty. Her beautiful and touching aquarelle, painted by the artist as her contribution to the O Sole Mio digital exhibition, expresses in multiple ways Sigurðardóttir’s concerns about this symbol of friendship, originally between two nations, and the freedom for all it has embodied for well over a century. Perhaps the artist has been reflecting on the meaning of freedom during the current lockdown. And now, considering the recent political events, we too may ask ourselves what freedom means in a time of escalating racial and political tensions. The monumental copper statue was a gift from a foreign country, from France to the people of the United States. Today, we might ask ourselves why the friendship between the USA and its allies has gone sour. Noteworthy in Sigurðardóttir’s delicate and sensitive watercolour is a feeling of sombre melancholy. Painted uniformly in grey as if the statue – that has welcomed countless immigrants and heralded their freedom in the land of opportunity – has suddenly become a shadow, no longer willing to reveal itself. Where has its exuberance and promises of a better future gone?

An innovative contemporary painter of still life, Lisa Milroy has an extraordinary ability to feel and sense the physicality of each object she paints. Milroy’s interest in objects is photographic and moreover her attention to and focus on objects often prevails over the significance of light, which in turn allows the objects to acquire their independence and take centre stage. This is totally opposite to the way the moving-image artist Sonny Sanjay Vadgama uses light in his piece Our Blood That Flows, shown in ‘O Sole Mio’ issue 09. So, in some ways it came as a surprise to me to see the group of photographs that Milroy created during the lockdown at her home and in which the prominence of light is indisputable. Here, her images of familiar and everyday objects find renewal by being fully bathed in rays of sunlight. Patterns and transformations of the objects happen when, for example, shadows of the glazing window bars interact with furniture or a person. This interaction between natural light and man-made objects constitutes a new direction for Milroy, which allows for new potentials not only in her practice but also in the manner the artist guides us towards discovering analogies.

Every day, like most people, I am learning and discovering the pleasure of doing tasks in new ways. I have come to think that knowledge and the sun function similarly, and the more one learns, the more possibilities open up, and therefore the more one gains access to analogies, just as the more rays of sunlight project on reality, the more nuances become evident.

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director