The Sun as Doorway to a World Within

We have time to think, we have time to observe and we have time to reflect. The world, our surroundings, work and family responsibilities, no longer clamour constantly for our undivided attention. We tell them to wait and they obey, how amazing! When was the last time I experienced such freedom for my mind to wander? Hmmm, maybe in the early 1960s, some years before the people of planet Earth sent astronauts to the moon, long before the mass protests of 1968, over fifty years ago. At the time, I thought that was how the world would behave forever.

It is said that children grow during their summer holidays, and I do not disagree. But what is it that makes them grow, both physically and in independence? Is it purely the sun and warm weather or rather the carefree environment that encourages them to undertake unusual activities and unforeseen adventures? For the sake of this conversation, I am asking myself whether childhood is a passage towards adult life or is it an experience that stays with us all through our life, through the many years and well into our older age? Dreaming about the past, our childhood, our youth, bygone eras, and even yesterday, is now not only possible but generally encouraged. Reviewing the past is not necessarily nostalgic or romantic, rather it can allow us to rethink and reposition other situations throughout life and ultimately help us to put things into greater perspective later in life. When I was a schoolgirl, I had the impression that time was passing very, very slowly. I loved my schooldays routine, but I also looked forward to the one day off we had in the week. Those were celebratory days to see my countless cousins, uncles and aunts and whoever else in the family would come along. In those days, family was the most important thing, friends were secondary to them and our trust was purely centred on the family, every member of which somehow contributed to our overall education, happiness, sense of security and confidence – I thank them all. Also, in those days, love, humanity and human support were infinitely more important than the apparently inextinguishable greed to possess limitless objects and the never-ending consumerism of recent years. We could perhaps say that the animate world of those earlier days was far more important than the inanimate one. Family gave us the strength and support which for me has been the backbone of my life, the force which gave me the resilience to maintain my positive attitude during all the years when I moved from one country to another, from one language to another and from one field of study to another. It always kept me keen and curious to go from one chapter of life to another, even decades later when I embarked on establishing an art foundation in a mega city like London, which I barely knew and had absolutely no contacts in. I think a full, busy, adventure-laden and happy childhood is when the seeds of a satisfying and productive life are planted. The more curious and adventurous a childhood is, the easier one finds the path to all kinds of possibilities and undertakings at later stages.

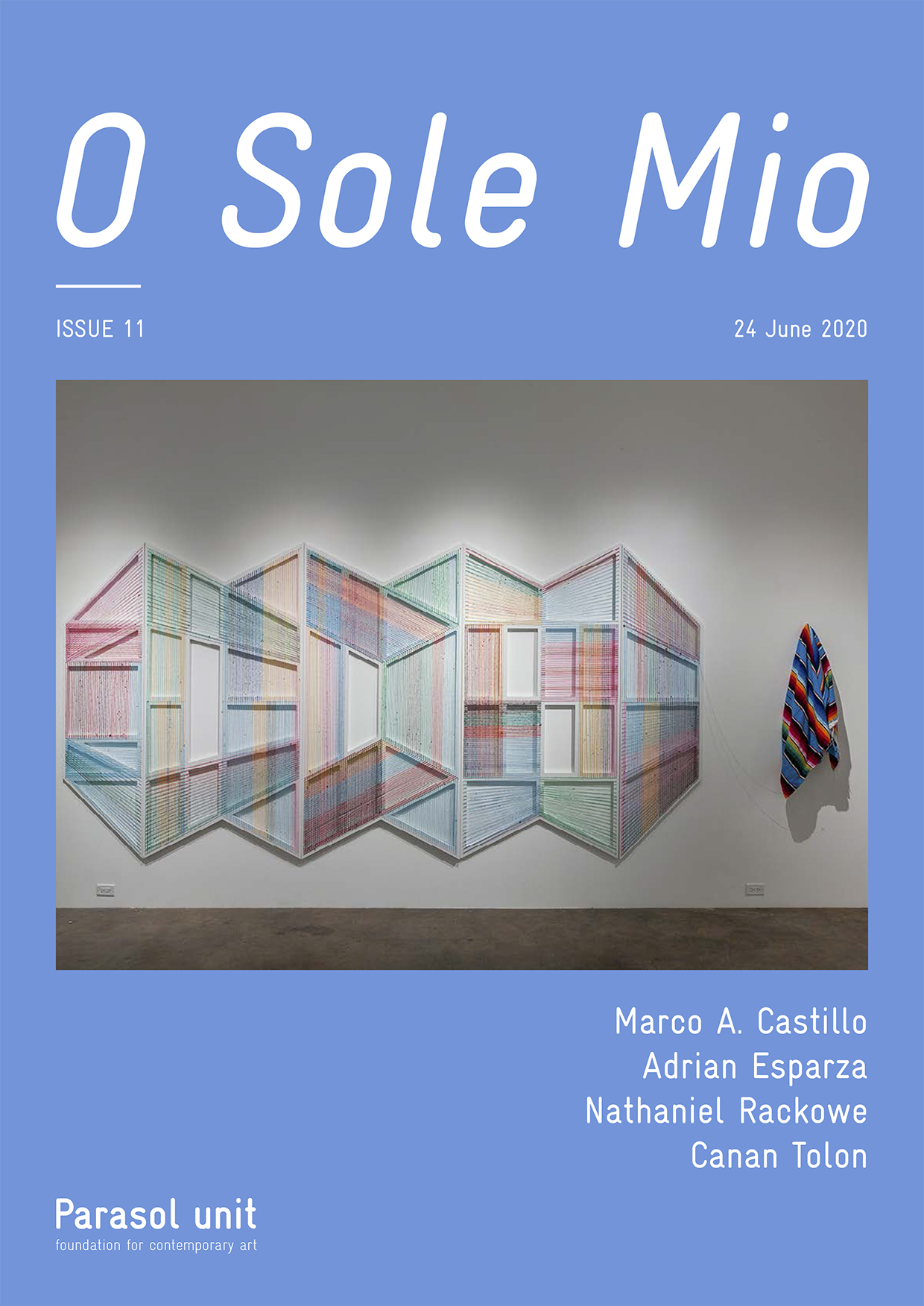

In each one of the works contributed to this eleventh issue of O Sole Mio by the artists Nathaniel Rackowe, Canan Tolon, Adrian Esparza and Marco Castillo, the vision or remnant of another world is vividly present. Whether the world within belongs to childhood memories, or a time past now envisioned as a remembrance of lapsed time, it is probably a time encapsulated and stored somewhere deep within us that may affect us throughout our life. I therefore offer these artists my grateful thanks for their thoughts, for having recognised in themselves the vision of a world beyond and for having shared it with us. The sensitivity and heightened feelings in each of these works has enriched me, but above all has revived my own thoughts of the past and the ensuing possibilities, something which I have probably neglected more than I should have, mainly due to an overloaded schedule in recent years.

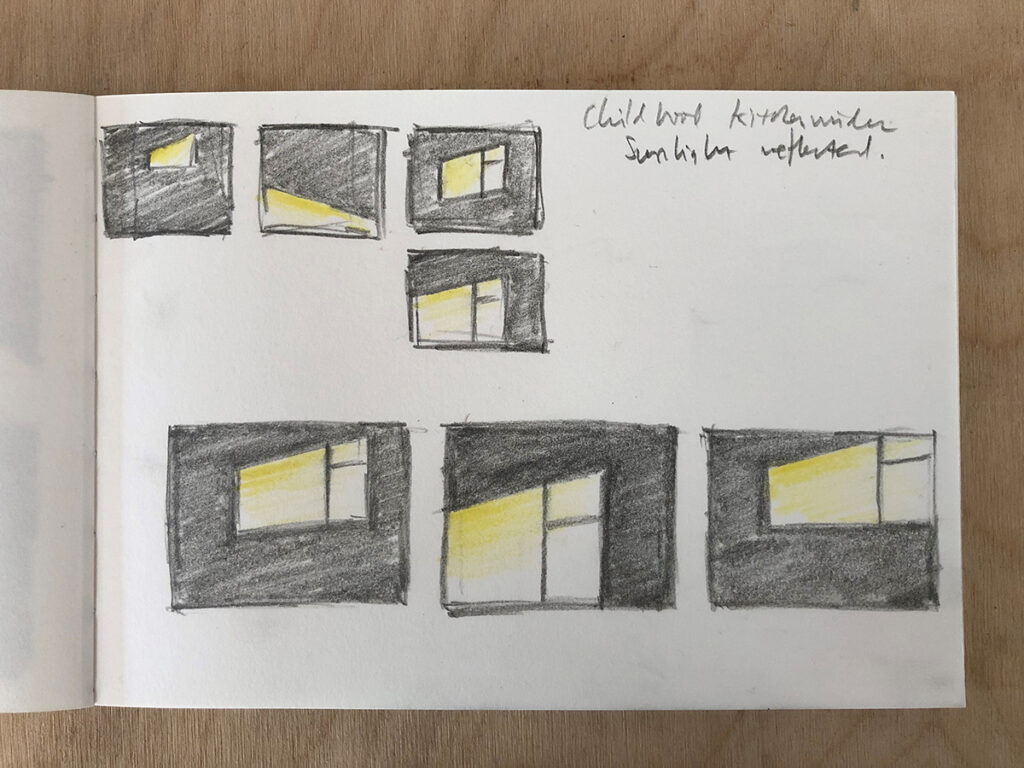

In Kitchen Window, Nathaniel Rackowe offers his childhood recollection of a carefree summer evening, lying in the garden of his family home, watching the sun’s reflection in the kitchen window. The very particular light expressed in his painting seems to have been something which has remained with him to this day. Not only has such light affected his personal vision of happiness and perfection, but it has continued to inspire and encourage the direction of his work.

Reading Rackowe’s explanation of his painting reminded me of my own earliest childhood memories, which I have carried like a treasure all my life and which have perhaps unconsciously influenced my decision to tackle the digital O Sole Mio exhibition as a way of exploring them during the stresses of the pandemic when we may all at times have felt trapped in the dark. My memory is of myself as an infant on a boat with my parents and siblings somewhere in the southern part of Iran. I clearly remember it was a warm day with afternoon-like sun in which we were all comfortably basking. This vision of sunshine has remained with me ever since and has surely kept my confidence high all through life.

Like Nathaniel Rackowe, Canan Tolon also dips into this other world to review some childhood memories. This time, though, it is not a lush and balmy summer evening scene in the family garden. Rather, it is from Tolon’s bed in the early hours of a day in a hospital ward of a polio clinic in southern France. No matter how different the two scenes might be, the common denominator is the memory of observing the glory and beauty of rays of sunlight and the hope and optimism it generated for each of them. The two images that Tolon provided for this issue have moved me to extremes. They do not speak only of light and darkness, hope and desperation in the face of life’s reality, they also consider the current political climate and in a poignant way express our common pain about racial prejudice as well as our hope for better days. Tolon’s concerns are not only personal, but rather and above all are collective and address the ills of our communities and of our world. Her concerns are also manifest in the volunteering work she has been doing during the pandemic in her hometown in California.

Sunroom by Adrian Esparza is a totally different way of taking inspiration from the sun as a way of entering this other world, while in a world of immense socio and cultural extremes. In the context of this discussion, Sunroom could stand for everyday life differences, along with all their ensuing possibilities and diversities, here in the simple vernacular architecture of an American town like El Paso and a craft traditional to the nearby regions of Mexico. Sunroom is a colourful and composite work created as a result of Esparza’s deep thinking. To create his work the artist employed a weaving technique specific to making serapes, the shawls or blankets worn in Mexico, using colourful threads from a serape, the other half of which hangs next to his work. In its current form, the complete work heralds a promise of renewal with fresh and new possibilities within the vision of an artist’s inner thoughts. Esparza lives and works in El Paso, Texas, just over a bridge from Mexico. Having been interested in the weaving techniques of making serapes, he has continually striven to bring into dialogue the past with the present, and tradition with the contemporary. As its name suggests, Sunroom belongs to a concept of domestic and functional contemporary living, yet through Esparza’s innovative and creative thinking, it is transformed into a poetic language with a conceptually far-reaching outcome with no function other than its own inherent beauty.

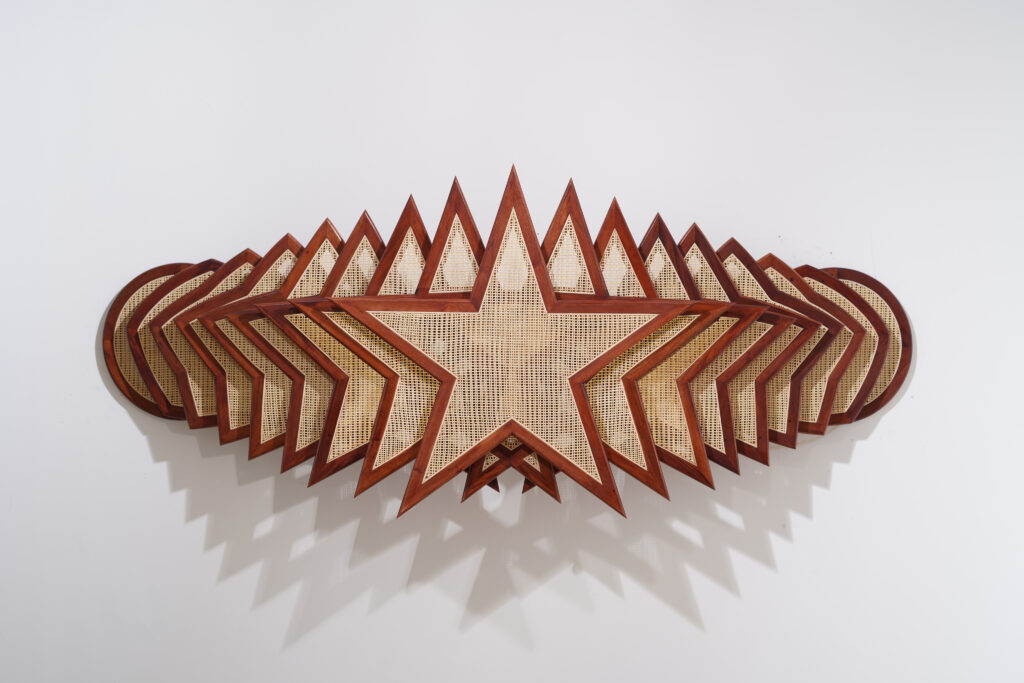

Marco Castillo’s memories of this other world – the hidden world that somehow comes along with us – are well expressed in his contribution to this issue of O Sole Mio. His memories go back to the artist’s birthplace, Cuba, with its uninterrupted tumulus of history and artistic influences accumulated over many decades. Of particular interest to Castillo is Cuba’s collective heritage of architecture and design from the 1960s and 70s – the first 20 years after Fidel Castro came into power. According to the artist, little remains of the creative output of the artists who had incorporated a great deal of historic and regional influences in their work. Castillo’s various works included here are entitled Córdoba in homage to Gonzalo Córdoba, one of the most important designers of that generation. This group of designers strove to create a modern living environment, albeit employing traditional materials such as rattan and mahogany, along with forms and shapes from earlier designs, such as the five-pointed star that became a symbol of communism. Castillo’s piece is a sort of metamorphosis from a circle to a five-pointed star and vice versa.

From private and personal childhood memories in the work of Rackowe and Tolon to the more collective concerns in the works of Esparza and Castillo, the works of these artists have been enlightened by their memories of the past, which eventually shed light on how to understand the realities of today. Whichever direction they go in, it seems early experiences are critical to our present existence and vital to our understanding of where we stand today and possibly where we are heading for.

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director