Homage to the Sun, a power that can lay bare Truth and Coalesce Creativity

Just the other day, someone sent me a pdf of an article by Thomas L. Friedman published in The New York Times of 30 May 2020, entitled ‘How We Broke the World’. It starts with the sentence: ‘If recent weeks have shown us anything, it’s that the world is not just flat. It’s fragile.’

How incredible that humanity as a whole has finally recognised this, after having recklessly abused practically everything that Mother Nature has so generously put at our disposal. Looking back, in 2019 we were in a different place – certainly not great or secure, but nevertheless we had other plans and perspectives on life – then here in 2020 there comes a minute but powerful virus called Covid-19 and our majestic world without the appropriate resilience falls literally flat. Like countless other people, I too see and feel dramatic changes in my life and day-to-day existence. I have kept in good spirits all along and have been going about my life and work, although I have terribly much missed hugging my grandchildren. Sadly, I also have to admit to feeling ashamed and guilty in relation to the younger generations, particularly the very young ones, because although problems have always existed in our world, my own childhood was a truly happy one. I was brought up having confidence in people and my surroundings, and the ability to enjoy everything in life, and I want the children of this world today to feel that way too. The shocking extent of this unexpected pandemic and now the recent racial tensions do not bode well for them having a similarly happy future. Instead of mourning though, let’s all put our hands and minds towards building a better world. We are now fully into spring with all its promise of renewal. Instead of remaining in the sorrow of mourning, I wish to encourage an optimistic and positive outlook on life. In many ancient civilisations and still today in some existing ones, white rather than black is worn to funerals.

Therefore, I offer here an image of daisies from my garden as a gesture of renewal, their white petals symbolising innocence and their yellow centres wondrously optimistic.

Interestingly, the works included in this ninth issue of O Sole Mio deal with the sun in different and unusual ways, hence their underlying content and connotations encourage us to consider them from various points of view, among them the human condition. Adel Abdessemed’s elaborate and impressive installation Shams (Sun, in Arabic) sees the sun as a power capable of projecting light on some burning truths in our society and the time we live in today. In his dramatic room-sized installation the artist clearly depicts forced labour as practised in certain parts of the world, where not only is it allowed but is reinforced under the watchful eyes of some merciless looking guards. Such a scene makes any viewer shiver in the face of the social injustice. The dichotomy between the title Shams, the sun that should herald hope and optimism, and the actual content of the work which reveals pure evil, highlights the kind of bare truth and reality check that is very much a hallmark of Abdessemed’s practice. Moreover, in this installation the artist uses clay, knowing that the fragile material is likely to disintegrate over time. For Abdessemed, the resulting dust from the work recalls the dissipation of the memories that humanity may have of countless brutal events and occurrences.

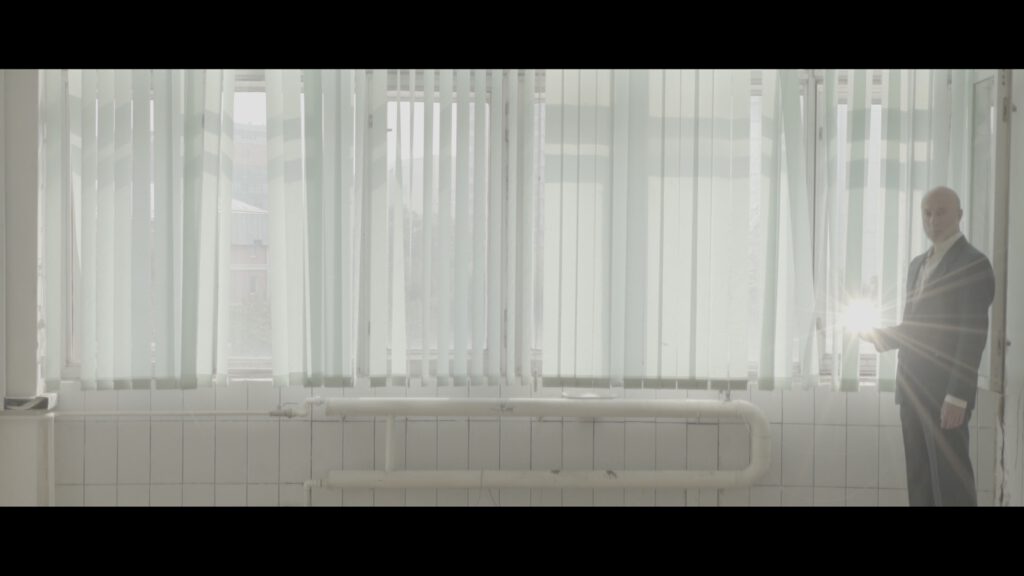

Sonny Vadagama filmed his moving-image work, Our Blood That Flows, in Moscow. Amid the eerie interiors of disused factory buildings, the work’s subject matter, as the artist explains, is the movement of light within those spaces and how it is connected to the wider theme of cosmology and evolution. It soon becomes clear to viewers that despite the presence of performers, in reality the main actors are light and the rays of sunlight streaming into these impressive buildings. These industrial structures, heavily laden with their past history and years of total physical abandonment, make ideal settings for any performance, whether it be the journey of the sun and light throughout the day or the uncanny scenarios danced or acted out by two performers, each of whom appears alone in different areas within the buildings. Whatever the artist’s intention or our own interpretation may be, we remain intrigued. For, as much as the sun and light are capable of laying bare truth, they are also maverick actors able to confuse realities and illusions and in turn allow for a fabulous creative act.

Sam Samiee’s sensuous installation, Gay Prometheus Stealing Lighters From Beautiful Woman, Women. Homage to Motherhood, is perplexing, uncanny and humorous. Lit with artificial light rather than by the sun, the scene here is set on a whimsical stage which lends itself perfectly well for Prometheus to manœuvre within his mental and physical space and to find ways of stealing lighters from women. Clearly Samiee, as an astute and innovative artist, plays here on several layers of associative meanings and in the process makes us reflect on the Ancient Greek Titan, Prometheus, who stole the art of fire-making from the Gods and passed it on to mortals. For which he was punished by Zeus, who had him chained to a rocky mountain and sent an eagle to feed on his constantly regenerating liver. As elaborate as the Prometheus myth, is Sam Samiee’s work title. There is a lot going on, such as a gay Prometheus who, visibly obsessed by the act of stealing, charms women and steals their fire-lighters – but then Samiee also pays homage to motherhood.

I recently came upon a book, The Secrets of Afro-Cuban Divination by Ócha’ni Lele. With gratitude to the author, I would like to quote a line or two from it: ‘I pay homage to the Council of the Mothers, the beautiful birds [witches] who are the Mothers of the forest. I give homage to the spirits of the forest who come to the aid of the Mothers of the forest again …’ This might tell us once more – whether we talk about supernatural forces, rituals, or we fantasise about a character from Greek mythology – that our senses and the human condition are profoundly intertwined.

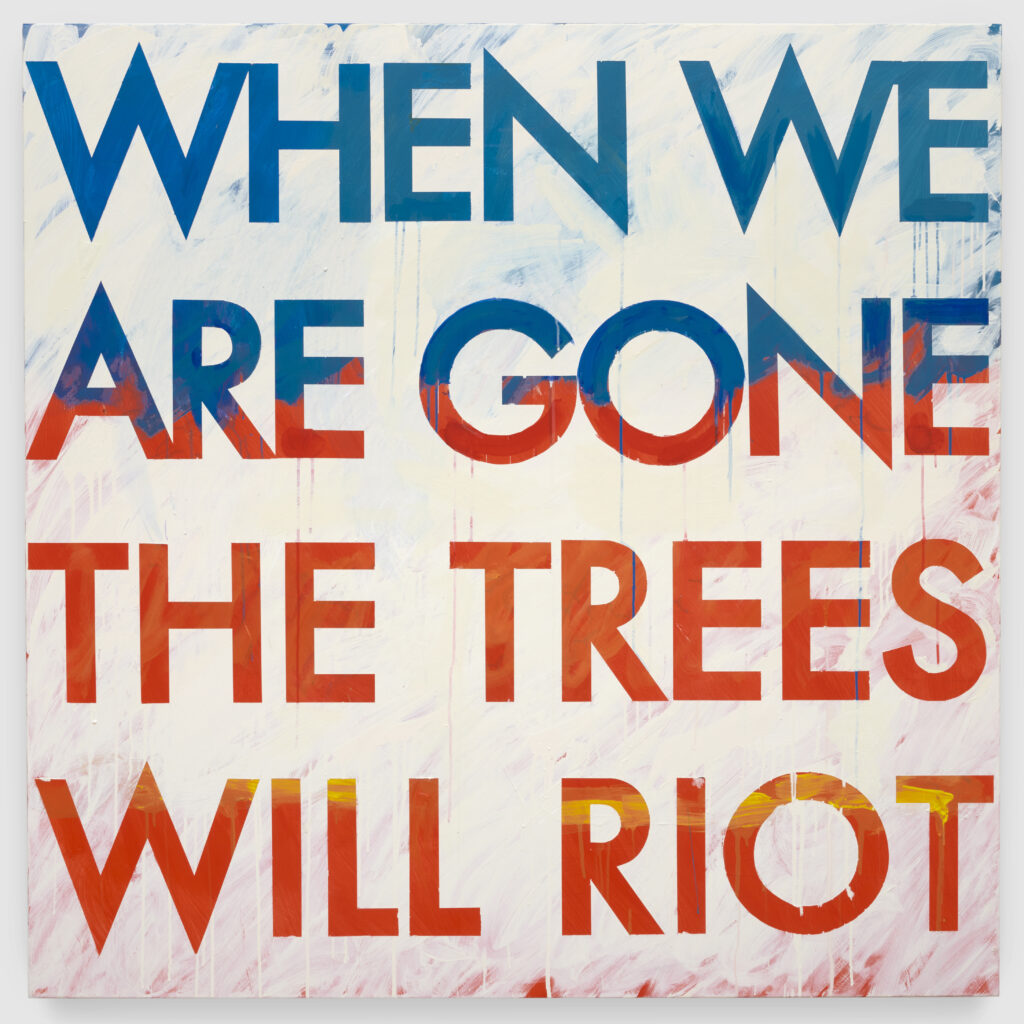

Robert Montgomery’s description of the almost hallucinatory state during which he executed his painting, When We Are Gone The Trees Will Riot, in part before he fell ill with Covid-19, then after his partial recovery, is perplexing and beautifully sensitive. On the one hand, Montgomery highlights the intensity of his personal senses in the face of a life/death scenario, and on the other hand he refers to the collective human fragility and unity that will eventually save us. Remarkable here is how the spirit of his poem comes alive, creating an almost figurative vision not only of the pandemic but also, co-incidentally, of the riots and manifestations of recent days. There is indeed nothing more poetic than finding oneself in the silence of lockdown with pure blue skies for weeks and imagining our protectors to be present in ‘the sound of the leaves in the trees’, or indeed imagining a better and united world.

All the contributions from the artists in this issue recommend or require, in various forms, clarity in our complex world, which has in many ways gone astray, and remarkably, Aaron Cezar’s reflections also function in tandem. How enlightening of Cezar to elaborate on the Ecuadorian artist, Oscar Santillán’s work Solaris. Glass, made by melting sand from the Atacama Desert in Chile, was polished into photographic lenses, 6.5 x 1 cm in diameter, which suggests that the desert landscape was then observed by none other than itself. Considering this work at the time of the Covid-19 pandemic and the riots seems quite fitting and revealing, as Santillán himself has said, ‘Only God Knows my Destiny’.

With such descriptions, we have good reason to wonder about the sun’s power of being simultaneously the culprit in so many different situations, from laying bare a brutal truth about human acts of abuse that eventually inform a monumental sculptural work like Shams; to conducting eerie scenes amid the distant beauty and uncanny atmosphere of some dilapidated buildings in Moscow; to revisiting a source of fire with the Titan, Prometheus, which turns upside-down that mythological fantasme; to experiencing the heightened senses of an artist/poet describing in his work the complexity of being ill with the coronavirus, yet finding beauty in the stillness of nature amid the streets of a mega city; to discovering a tiny work of art made of desert sand, which could in theory observe our acts and behaviour.

Like many others during the current Covid-19 pandemic, and more than ever before in my life, I have been reflecting on human life experiences. In this process, I have been incredibly enriched by the many thoughts and innovative works provided by the artists. This whole situation has made it clear to me how important it is to be human and to feel human. Because, whether life experiences have been brutal, speak of a distant and ancient past or of diverse and different cultures, seeing human experience through art or by coming into dialogue with ourselves in the face of the current pandemic and struggling with it, much of it remains as an unresolved puzzle. How interesting to think that the sun could shed light on some of these puzzles and guide us to better see the truth.

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director