An Abundance of Light, an Abundance of Joy,an Abundance of Hope

Seeing so many fields of colza (oilseed rape) so early in the season this year comes as a most welcome occurrence – an almost surreal gift. For in this mountainous part of the world, colza flowers usually make their irresistible presence visible to us somewhat later, in the month of May. In every one of the many seasons I have been lucky enough and grateful to witness them, the sight of the dazzlingly yellow fields has, more than anything else, meant to me a pure celebration of light, hope and life. A dichotomy exists, of course, between the seemingly sudden appearance of these exhilaratingly beautiful yellow fields and the reason for their cultivation, which is the production of rapeseed oil through a mechanical process.

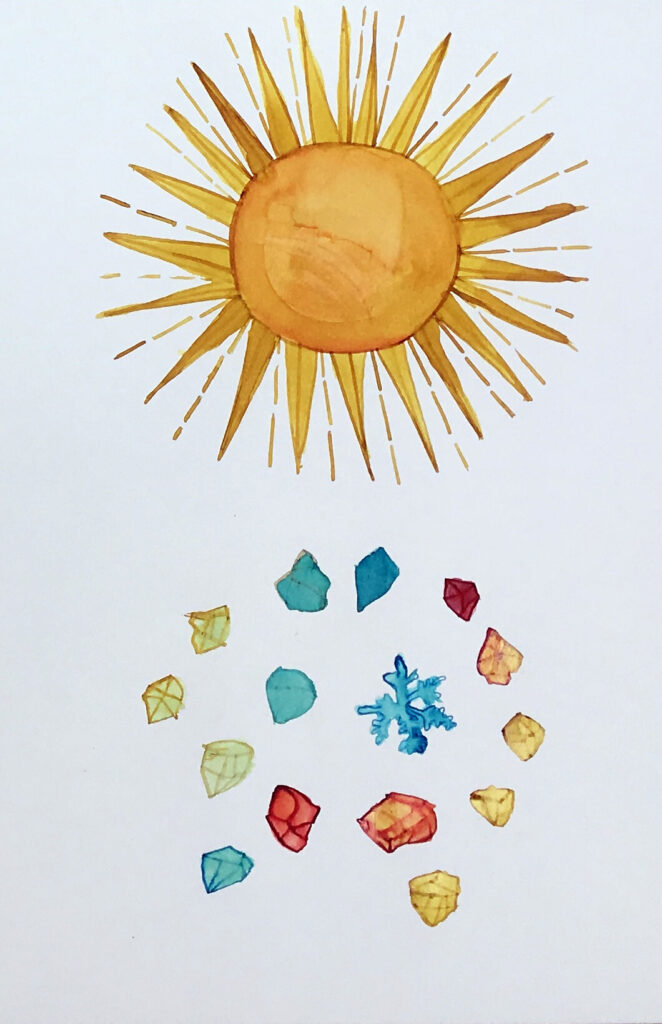

The luminous experience of that startling yellow struck me once more as I was looking at Christine Rebet’s marvellous drawings, Archaeology of the House of Dreams, and Julian Charrière’s impressive photograph, Sycamore from his First Light series, which the artists have contributed to our digital O Sole Mio exhibition. The kinship was further strengthened when I made another connection: the fields of colza, Rebet’s drawings and Charrière’s photograph all in some way exemplify a tension between nature and technology, a tension that is not only physical, but also reflects a psychological dogma that has pervaded our existence since the Industrial Revolution.

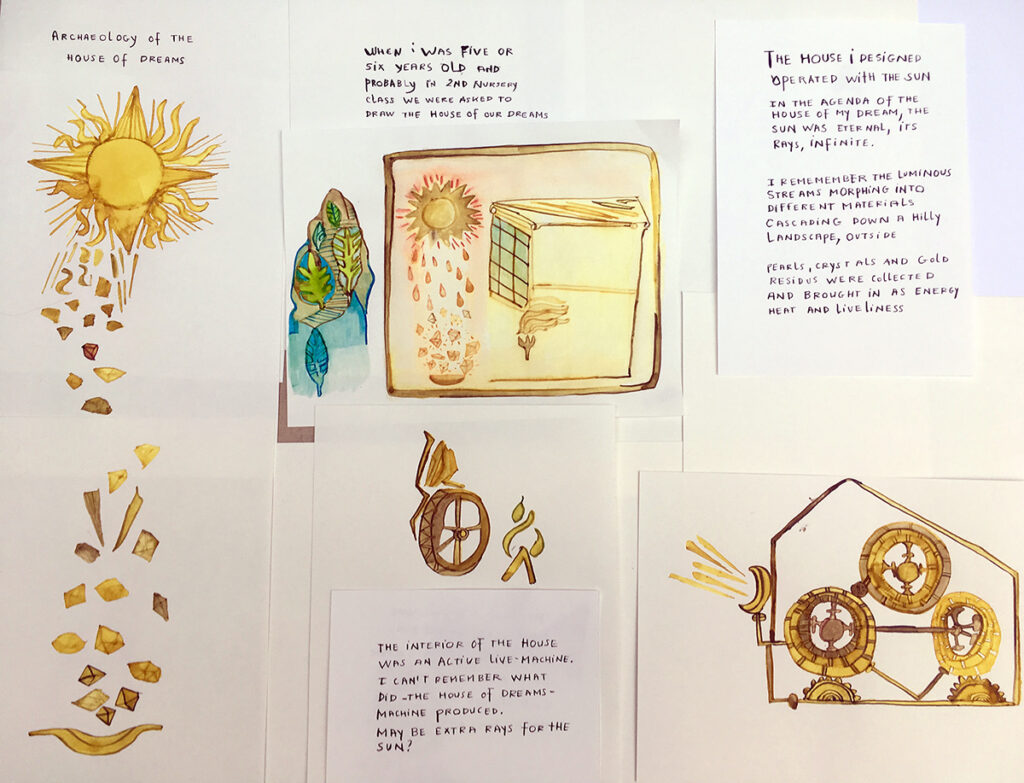

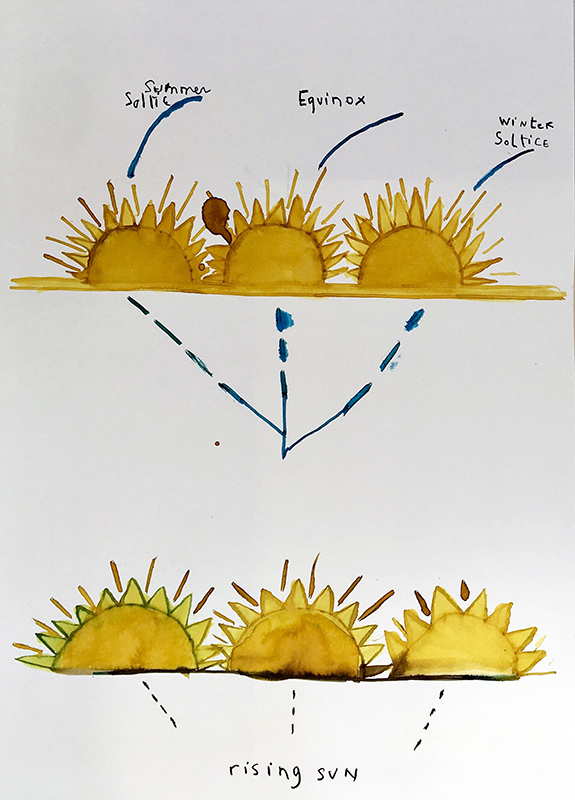

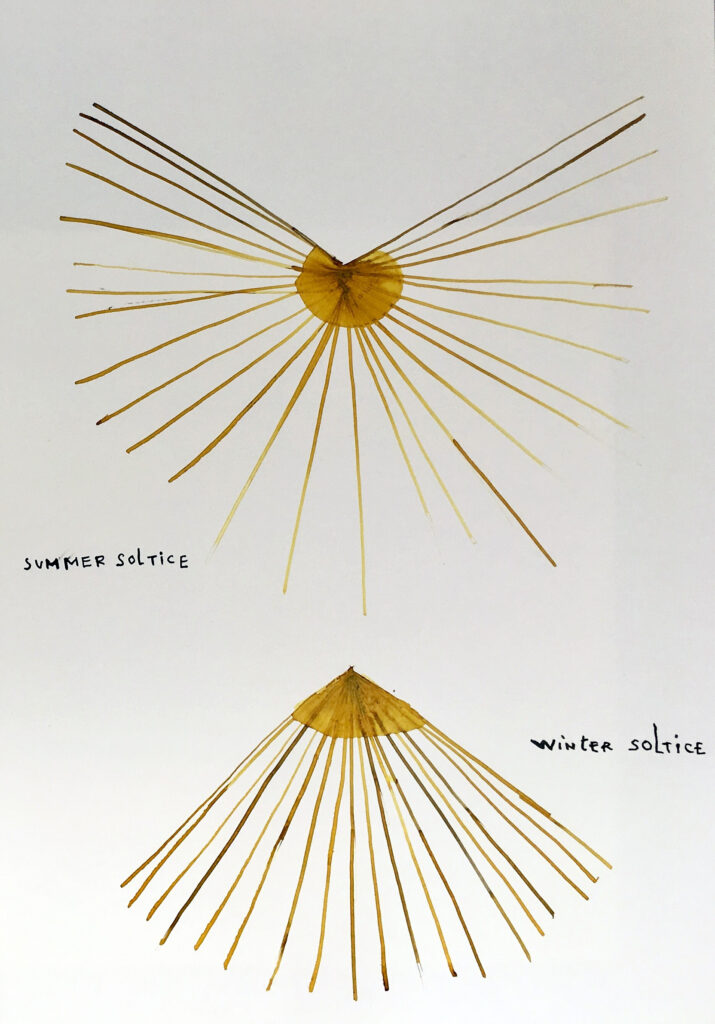

Archaeology of the House of Dreams tells an intriguing story with multiple images and various brief texts spontaneously brought together on paper in April 2020 and clearly recalling a childhood vision. When Rebet was a young child, her school class was asked to draw the ‘House of our Dreams’. Rebet presented a house that was operated by the infinite rays of an eternal sun. From the vantage point of today, Rebet’s delicate drawings suggest a metamorphosis of nature, architecture and machine working in unison, which has become a hallmark in her work.

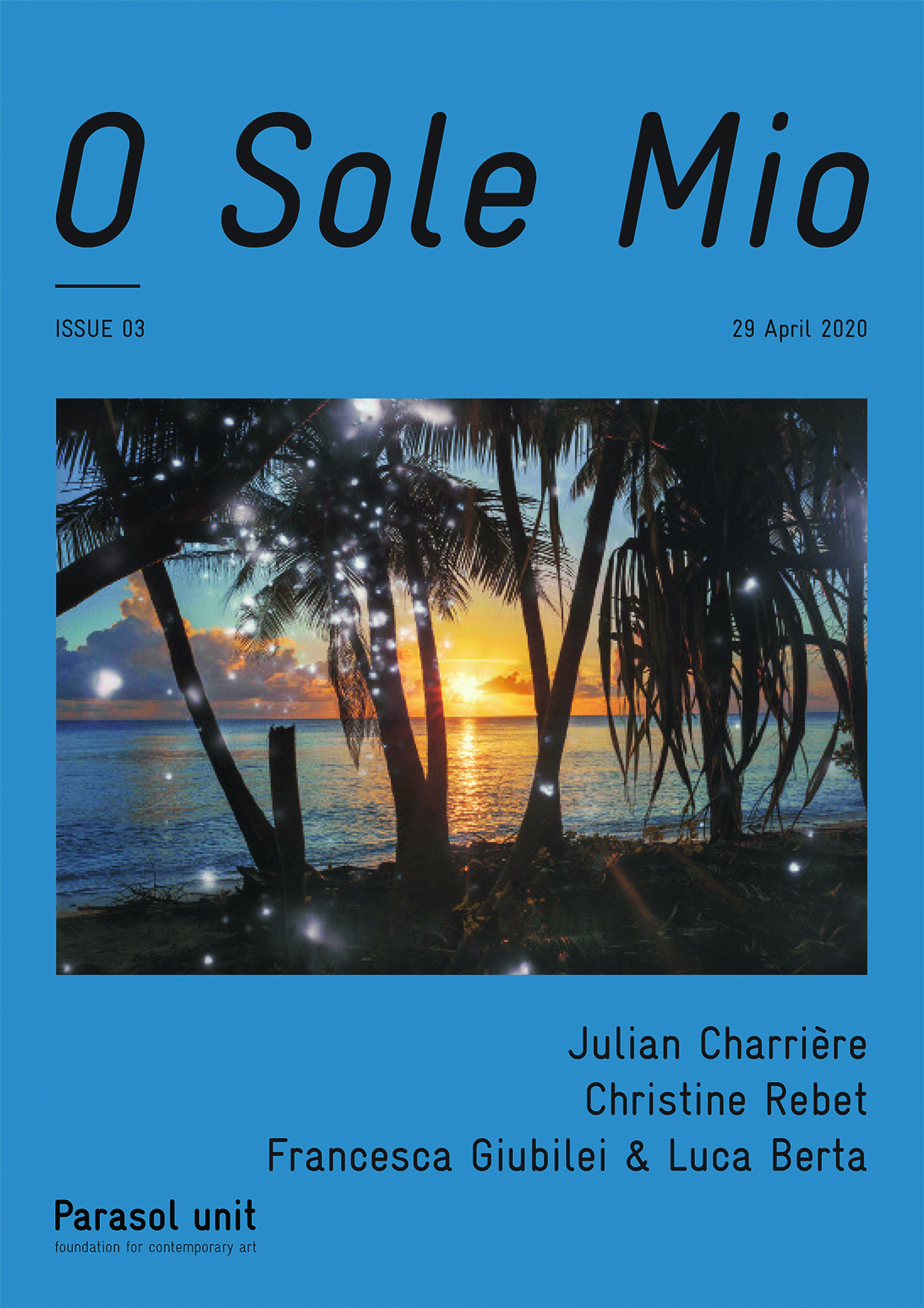

Julian Charrière’s Sycamore photograph from his First Light series was taken in 2016 during one of his exploratory trips to Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Against a backdrop of idyllic tropical scenery with a blinding sun on the horizon, Charrière lets us observe the remnants of atomic bombs and the dramatic effect they have on vegetation and landscape. In all its seemingly pristine beauty, the bittersweet relationship between nature and technology is somehow persistent, which reminds me of Leo Marx’s book The Machine in the Garden from 1964. Nonetheless, I am overwhelmed by the energy and optimism so clearly alive in every human heart and ensuring that the natural world will prevail.

For the Reflection section of O Sole Mio, art professionals are offered an opportunity to express their thoughts. In this issue, Francesca Giubilei and Luca Berta of the Venice Art Factory in Italy have formulated some touching and positive thoughts, together with an energising image of some gondoliers at play, which speaks of the vitality of life in the face of imminent isolation, perhaps even the seemingly impossible. Bringing into dialogue the two special Italian cities, Venice and Naples, Francesca Giubilei and Luca Berta celebrate the universality of art and cultures that see no borders.

It is fitting here to thank Christine Rebet, Julian Charrière, Francesca Giubilei and Luca Berta for their remarkable vision and contributions that have made possible this fabulous issue of O Sole Mio. So, in the face of the most drastic challenges, let us remind ourselves that light and its invincible strength remains always with us.

Ziba Ardalan

Founder, Artistic and Executive Director